Helpful Financial Concepts For Increased Clarity

“The limits of my language are the limits of my world”

– Ludwig Wittgenstein

We’ve been looking at some “back of the envelope” financials, and how to respond to the inevitable surprises and assumptions that emerge.

This might make you want to run some tests and experiments, research crucial assumptions, or even change the way your business makes and spends money.

What we need next is some new terminology – ideas and concepts that will help you describe what you’d like to add or improve in your business.

Some of these are essential parts of finance, others are interesting ideas taken from successful startups.

Either way, if you have the words to describe a trap or opportunity, you’ll be much better at identifying them well in advance.

To be be clear, you don’t have to be an expert in these, but you need to know enough to be able to work with an expert on these.

Let’s start with some helpful concepts for financial clarity…

The three financial statements

For the purposes of “the back of the envelope”, we really need the figures mentioned so far: how money flows in, where it gets spent, when do you break even, and what assumptions are you using.

This is a good start, but a proper company will be looking at their financial health through three different perspectives.

To do this, they use three different financial statements, usually prepared by an accountant.

We hear you thinking “uh oh, will I need to build these too?”, and for the time being the answer is more like “no, but you need to be able to read and interpret each of them”.

The three are known as a Cash Flow, an Income Statement and a Balance Sheet.

A Cash Flow shows each dollar that entered and exited your business.

This shows money coming in and money going out, but does not offer any insight on why it’s happening, or what that money is going towards.An Income Statement (or Profit and Loss or P&L) shows when you “earned” and “spent” money in your business, even if it’s different to what your bank account might tell you.

A Balance Sheet isn’t so much about cash, but rather about the value of all of your assets and all of your liabilities.

So if you own a property and it goes up in value this year, or if your brand becomes significantly more famous, it will show up on your Balance Sheet but not your Cash Flow, as it hasn’t brought in any money quite yet.

Vice versa, if your property becomes more and more run-down, but you don’t spend any cash on repairs, it will go down in value on your Balance Sheet but not really register on the other two.

You’re thinking “Why do I need to know this? Why does this affect me?”.

Because looking at all three of them lets you see the real story of your financial health.

If you only looked at one, you could get tricked.

Let’s say in January, a bunch of companies like Spotify and Netflix email you with an offer – instead of paying $20 a month for each of these, pay upfront and it’ll be $200 for the year.

You’re paying 10 months’ worth today, for 12 months’ worth of streaming.

If you’re definitely keeping these subscriptions, then this is a great deal.

On your Income Statement, we could see the cost per month go from $20 down to $16.67, every month, for the year.

On your Cash Flow however, you’re going to have a hugely expensive first month, where you might spend thousands of dollars at once, but then enjoy the rest of the year “for free”.

The offer feels both cheap and expensive, depending on how you look at it.

Let’s say you are a freelancer, and this week you’ve spent 50 hours on paid client work.

You’ve worked hard, and for a good rate.

However, you won’t get paid for another three weeks.

Has it been a good week?

Alternatively, let’s say you’re a business owner and haven’t needed to spend much money – sales are slow so you’ve been using up a lot of the stock in your inventory.

Has it been a good week?

A startup might be making a lot of progress with customers who are promising to sign up, but if it runs out of cash, game over.

A department store might be making good sales, but their assets (inventory and equipment) are quietly losing value every year, which could leave them with an overall loss.

A cashflow might tell you that you spent $70 to fill a $100 order.

A Profit and Loss then breaks down how much of that $70 was on cost of goods versus overhead costs – which can be a huge red flag.

What about your non-cash expenses like depreciation?

It might not be a payment, but it’s certainly an expense that needs to be monitored, otherwise you’ll be stunned when a valuable item suddenly needs to be replaced.

If you measure purely the money in and money out, you’ll get the wrong impression.

If you look at the overall position of your business, you get a better idea.

Drivers

Drivers are what push or influence a particular number – what made it the way it is?

e.g. why did we sell 200 products this month?

Was it from 200 individual customers?

Was it from a promotion or campaign?

Did we ramp up our Google Search traffic or social media presence?

Did we add some wholesalers or distributors?

Did we add some salespeople?

We want to understand what’s going on beneath the surface, so that we can work out what might need to happen to change these numbers in the future.

i.e. if we want to grow to 400 sales per month, what would drive that change?

People often show us their ramped-up growth trajectory with numbers climbing steadily by the month.

Ok…

Maybe that could happen?

But why?

What’s changing in month 4 that makes you go from 290 orders to 330 orders?

It’s definitely possible, but what caused it?

Put another way, if you can’t explain what drivers are going to change, why would we assume that the numbers are going to change?

We like to think of Homer Simpson misunderstanding why his investment was going well:

“This year, I invested in pumpkins. They've been going up the whole month of October and I got a feeling they're going to peak right around January. Then, bang! That's when I'll cash in.”

And as his broker chastises him:

“Homer, you knuckle-beak, I told you a hundred times: you've got to sell your pumpkin futures before Hallowe'en! Before!”

As a number increases, we tend to celebrate it and immediately attribute it to our plan working well.

In reality, that number could have increased for all sorts of reasons, which we need to understand in order to keep our progress going.

The way to find your drivers is to pick a figure and ask “why is that?” repeatedly until you find the root cause.

That’s the driver.

e.g. our costs are higher than last year, because our wage bill is much higher, because we hired three new team members.

Therefore, number of team members is a cost driver.

Sensitivities

As you know first-hand, things change very suddenly in startups.

Opportunities come out of nowhere, or disappear just as quickly.

One right post can suddenly send thousands of prospective customers your way, and one new geopolitical decision can decimate your revenue.

We want to identify the most “sensitive” figures, the ones that have a large impact on the financials.

i.e. where does one client make/break your profitability, or one team member make/break your staffing costs, or one currency fluctuation erode/double your margins?

We want to list these sensitivities out, so that we can see their effects and plan some responses.

That way, when life happens and plans change, we can still predict how much money will be earned and spent by the business.

Most importantly, this help us ensure that we’re never “over a barrel”, where a single supplier, partner or competitor can destroy our viability.

Scenarios

We can’t be 100% confident in predicting the future, but we can create some hypothetical scenarios and see how the numbers stack up in each of them.

When times become tough, you’re probably going to start cutting back on expenses.

First the luxuries, then the conveniences, then some necessities.

Hopefully in that order.

That means there isn’t just one version of the future; there are several.

There’s the version where you make minor adjustments, the version where you cut half the team and move back in with your parents, and a few versions in between.

We want to understand what all of these look like, without judging them, and with honest numbers.

For example, your rent could be $10k per month for a large office, $5k per month in a nice coworking space, $3k per month in a bad coworking space, or $0k per month in your garage.

Your payroll could change through pay cuts, dropping to a 4 day week, making some people redundant, or outsourcing some roles to cheaper countries.

And this is where the trade-offs come in.

Would you pick the worse coworking space if it prevented a pay cut?

A great way of doing this is with a best case, average case and worst case scenario.

To do this, we copy our financials into a new tab, then rebuild the assumptions table with more optimistic estimates about customer numbers, group sizes and costs, then do the equivalent with pessimistic estimates.

What you’ll probably notice is that some numbers change a lot, and other remain pretty constant – we want to learn about the numbers that have a big impact on our profits.

Usually the big variables are on the revenue side, as in the number of buyers in the market, purchases per customer, and the price you set.

A change to any of those figures probably has a big impact on your bank account.

Contingencies

Sometimes in finance, people use fancy words for basic ideas, to make them sound more acceptable.

If you’re seeing that your model has some sensitivities, you might add in some money for contingencies, which is the fancy word for “spare money in case things go bad”.

This might be a sum of money, or an extra 5% on top of your costs, and is there to protect you when something inevitably goes wrong.

Contingencies are great to build in when moods are high and there’s money in your accounts.

They are a way of putting money aside for a surprise, because when you’re surprised and stressed, new pots of money can be hard to find.

Metrics and Indicators

Continuing on with fancy names for basic ideas, “metric” comes up a lot, and means “thing that you measure”.

Your life is full of metrics, and not all of them are meaningful.

Sometimes we use “vanity metrics”, where we focus on measurements that make us sound and feel good, even if they don’t relate to anything meaningful.

e.g. the number of visitors to your website, the number of customers you have served, the number of awards you have won.

They are nice and they make you look good, but if they don’t give us a meaningful or insightful story, then they become hollow.

Some metrics can become Indicators, where they tell us something useful about what’s happening in our business or our broader market.

A recent example is the “Pentagon Pizza Index”, which tracks how busy the four pizza places near the Pentagon are at any time.

When the US is dealing with a serious geopolitical event, they usually need the team to work later and end up buying dinner for everyone, so all four pizza places spike unexpectedly at the same time.

Therefore, nerds can watch those four pizza places and determine if the US government is likely undertaking a high-stakes mission at any given time.

Is it a perfect correlation?

No.

But is it a decent, albeit unintentional indicator?

For the moment, yes…

Goodhart’s Law

Goodhart’s Law states that "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure".

If you pick a metric and turn it into a goal, you will probably start manipulating and influencing the goal through your actions.

e.g. if the metric you’re focused on is “customer re-order rate”, you might start sending 5x more emails to your existing customers or offering discounts or free shipping.

This would likely lead to more sales in the coming weeks…and also annoy a lot of your list, or even ruin your margins through those discounts.

Or you can focus on creating social media content that attracts views, interactions or more followers, but if those aren’t coming from your real customers, they won’t translate into increased sales.

For this reason, you’ll want to pick a group of indicators that represent your underlying goals, rather than one number that can be twisted out of significance.

The Pentagon Pizza Index worked because the Pentagon seemingly didn’t notice or care, but if it becomes a focus, it will no longer be a helpful predictive indicator.

Payables vs Receivables

It might sound obvious, but it can trap otherwise intelligent founders – different businesses have different gaps between when they buy something and when they pay for it.

For example, you might buy ingredients for a catering order today, but then not send your invoice until next week, with 30 day payment terms.

That means you’ll (hopefully) get all your money back and more, but for the next 30ish days, you’re basically lending money to your customers.

For one order it’s probably ok, but imagine you take on 10 of these jobs this week, all of them paid back in 30ish days.

As your business grows, you’re suddenly spending a lot of money long before you get it back, and it can become a real risk.

Vice versa, you can use this to your advantage, receiving payment up front from your customers, but paying your suppliers in 1-2 months time.

In the long run, this probably feels unimportant, but in the immediate future it can cause headaches, and leaves you holding all the risk while someone else holds your money/inventory.

Your job is to understand how payment terms work in your field, both when you’re a buyer and a supplier/vendor.

Then, you get to set or negotiate payment terms in the future.

It might be a slightly tense moment on occasion, but it’s usually when spirits are high, rather than arguing over late payments or invoices.

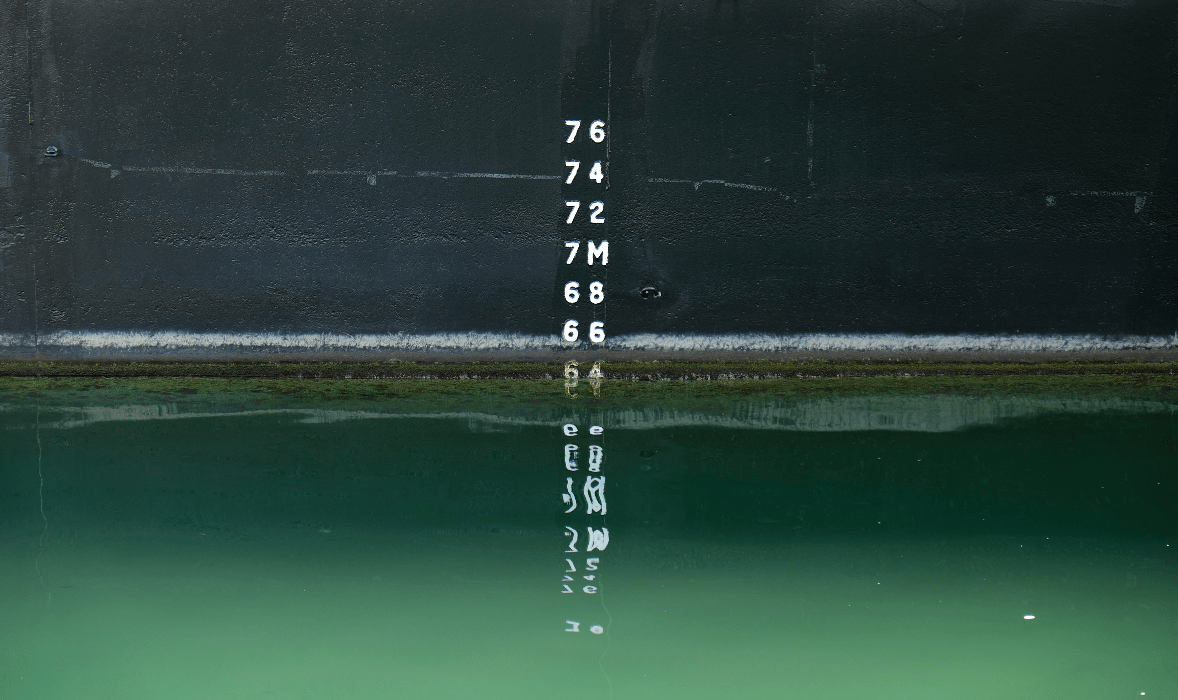

All of these concepts, metrics and indicators might sound complicated, but it’s a bit like driving a car.

Most of the time, you’re looking out the front windscreen, with glances to the rear-view mirror and side mirrors.

Then there’s your dashboard, which has a few different indicators:

Speedometer: how fast you are travelling

Tachometer: how hard the engine is working

Fuel gauge: how much fuel/battery is remaining

Odometer: how far the car has travelled in total

Trip meter: how far the car has travelled recently

Temperature gauge: how hot/cold the engine is

Engine light: something about the engine isn’t quite right

Door light: one or more doors isn’t properly shut

Seatbelt light: someone’s seatbelt isn’t on properly

Headlight icons: which type of headlights are currently on

As a driver, you’re periodically glancing down from the windscreen to see how the car is performing, and to spot anything unusual or dangerous before it leads to trouble.

That’s what you’ll eventually do with more detailed financials; learn what these indicators mean, and which ones require your consistent attention.

Financials aren’t a chore and they’re not for other people, they’re for you.

Is it a chore to look at the dashboard of your car?

Of course not, the dashboard is there to serve the driver.

The numbers and indicators tell you what you’re currently doing and how much longer you can keep going – all designed to make your life easier and avoid catastrophe.

There’s no benefit to trying to “trick” your fuel gauge or make your speedometer look more pleasing, they’re just telling you the facts so that you’re equipped to make good decisions.

But you also don’t need twenty indicators and icons on your dashboard either, you want enough to be able to take in the relevant information at a glance.

That’s what we’re trying to do here.