Financials After The “Oh Shit” Moment

At Evander Stategy, we teach financials in an upbeat way.

This is partly because financials are often taught in a boring way by most programs, but also because entrepreneurs have some decidedly un-fun experiences with money.

These are called “Oh Shit” moments – when you suddenly or slowly realise that you have a big, costly problem, usually without an immediately obvious solution.

If you’re thinking “why do they have to swear, surely this could be called an ‘uh oh’ moment’, then you haven’t experienced an “Oh Shit” moment.

When they hit, politeness is the last thing on your mind.

It’s not an accounting problem, it’s not about correcting errors on a spreadsheet, it’s a sinking feeling as you comprehend how bad things could soon become.

These are a “when, not if” part of business.

They’ll happen, sometimes for reasons out of your control, and so you need to develop a way to process difficult situations.

Positivity is helpful but isn’t a strategy.

You’ll need some scenario modelling, some good questions, some validation and a range of options to explore.

The “Oh Shit” moment for your financials

Right now, you probably have some initial reactions once you see your Back Of The Envelope numbers taking shape.

Some might be good, a lot tend to be bad or uncertain.

It could include revelations like:

We have way more costs than we thought

I have no idea what some of this stuff is supposed to cost

We can charge way more than we thought

How much do other businesses like us tend to charge?

Our breakeven point is not what we assumed it would be

Our finances are surprisingly fragile

Our finances are surprisingly hard to ruin

This is way easier than I anticipated

This is way more complicated than I anticipated

Why did no one teach us this before?

The best part about the “Oh Shit” moment is that you’re having it right now rather than next year.

At this stage, everything is what Mario Forleo calls “figureoutable”.

Maybe it can be changed, or maybe it’s a constant reality of business you need to work around.

You have time to make changes, time to do more research, time to talk to a coach or a group of friendly advisors.

This is much better than having the moment when you lose a lot of money, or get caught off guard by extra expenses once you’ve made big investments.

Your initial numbers are helpful, however they are not reliable.

For a number to be reliable, it needs to be validated – based on evidence, not a gut feeling.

So before we go rushing to conclusions, positive or negative, we first want to check if our numbers and assumptions are correct.

What do we need to validate?

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

Validation is in your interest – to protect you from nasty surprises.

And yet, a lot of founders treat it like a chore or an affront.

When people say “what do I need to validate?”, they sometimes really want to say “what’s the least I have to do to say it’s validated?”.

This is a bad question, but to answer it anyway: the smallest version of validation is to check your most crucial assumptions.

These are the assumptions in your thinking which, if wrong, would completely pull the rug out from underneath you.

They could be topics like:

How many customer actually exist?

Does anyone want what we sell enough that they’ll switch brands?

How much does it truly cost to serve a customer?

Can this break even in the next two years?

The more confidently you answered those in your head, the more important it is to check the answer

Broadly speaking, financials are made up of maths and assumptions.

Maths are the calculations and the way you add/subtract/multiply/divide figures to reach a conclusion.

Assumptions are the guesses that go into choosing each of those figures in the first place.

Both are important to get right, and different people can give you different sorts of advice.

Your accountant can say “hey you might have forgotten to factor in a few costs” or “postage costs are part of COGS”, whereas your peers and colleagues can say “hey you’re paying way to much for…” or “hey you need to allocate more money in…”.

This makes use of Cunningham's Law, which states "the best way to get the right answer on the internet is not to ask a question; it's to post the wrong answer."

If smart people see your wrong maths or assumptions, they almost can’t help but correct you with a better answer.

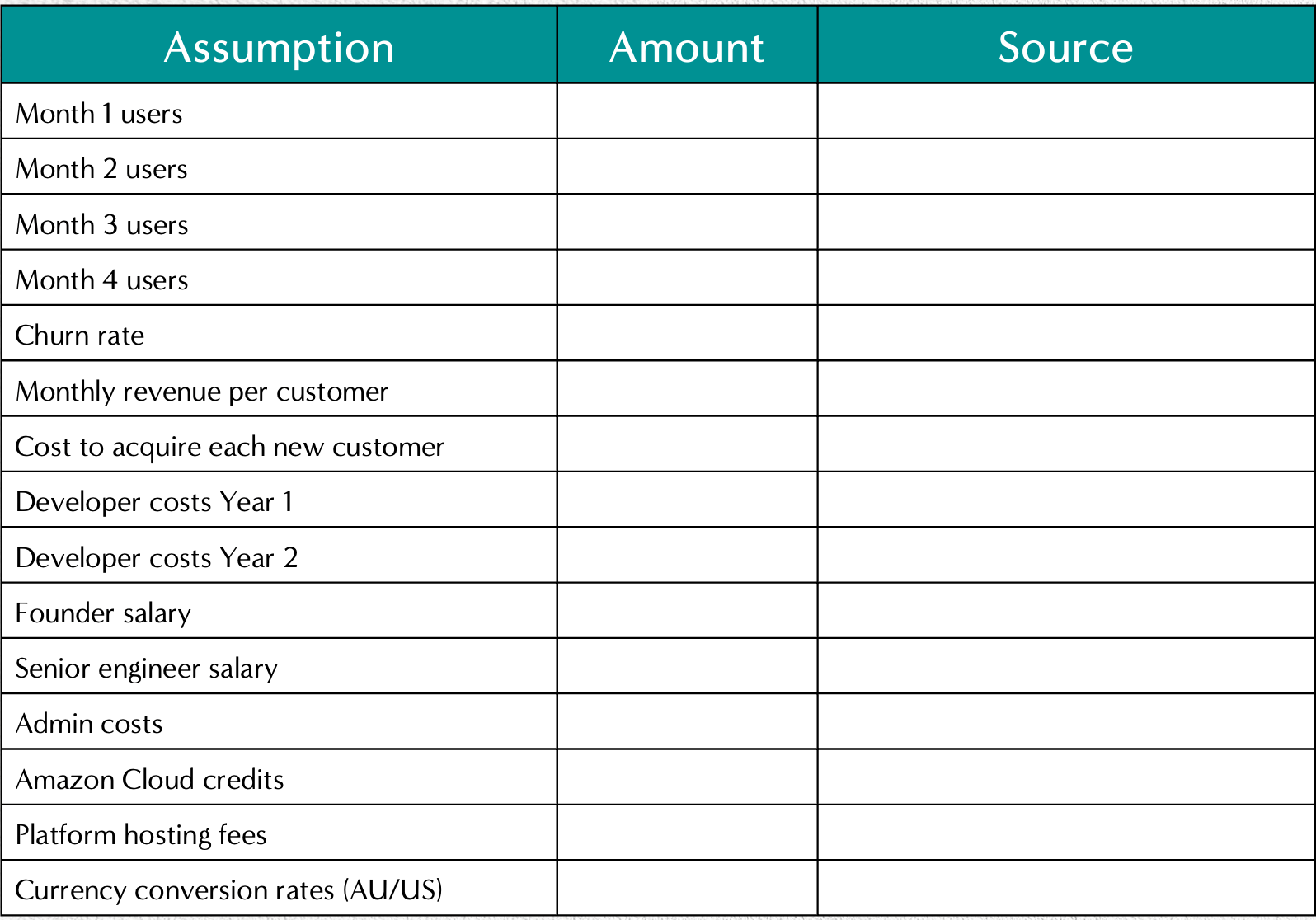

Assumptions Tables

Earlier we looked at the maths of your business with those cost, revenue and margin calculations.

Now we want to improve the quality of our guesses, and the best way to do that is with an Assumptions Table.

These are simple and yet profound – a list of all your guesses, what you’re guessing and where it came from.

As a founder, you’re dealing with a mix of rock-solid facts, educated estimates and total guesses.

This is fine, so long as we keep track of which is which.

e.g. the price of fuel, the hourly rates of key staff, insurance costs depending on how big you grow, currency exchange rates, etc.

These are allowed to change, but if we don’t stay up to date, our figures can wildly diverge from reality.

Building an assumptions table is laughably easy, the hard part is properly researching all of the gaps that you don’t know.

We need a table with 3 columns: Assumption, Amount and Source.

e.g. Postage, $6.95 per order, based on XYZ Delivery Co, August 2025

Or Churn rate, 10%, based on interviews with 3 other SaaS founders, in May 2025.

You’ll realise how much you already know, how much is based on shaky evidence, and how much is based on vibe and rough estimates.

As you’re building your calculations in a spreadsheet later on, we’ll use the numbers in this table.

That way, when your estimates get updated, all of the calculations will update as well.

So if postage goes up by a dollar next year, you only need to change the postage figure in this table and all the rest will instantly update to the correct number.

Yes, it takes a little longer to set this up at first, but it’s better than baking old numbers into your calculations that turn into shocks later on.

From an external perspective, looking at someone else’s assumptions table is one of the fastest ways to check their thinking and how realistic they’re being.

It’s hard to deduce their maths and formulas, but their assumptions are easy to read, and will stand out if they’re wildly out of touch with reality.

That’s all the more reason to keep your assumptions in one place, for your own clarity and to invite helpful suggestion.

How to run helpful tests

There will be some assumptions that can’t be researched online, they require you to run a test.

This is particularly true for any new technology, new business model, or serving a market who haven’t bought what you’re selling before.

Tests don’t need to be complicated to be useful, but it’s important that you don’t cheat to get a nice-sounding result.

You might be stunned to see how many founders skew their experiments to justify the course of action they want to take, even though these tests are only here to protect them.

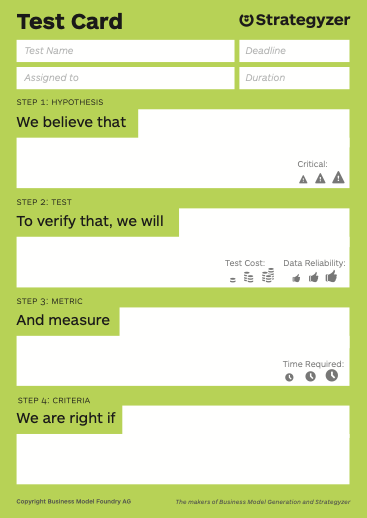

One of the best ways of designing a test is with four prompts, like the ones in a Strategyzer Test Card:

We believe that (naming your crucial assumptions)

To verify that, we will (stating what action you’ll take)

And measure (what meaningful metrics you’ll track)

We are right if (setting a pass/fail criteria in advance)

These are great because you build them BEFORE running the test, forcing you to determine what would fairly be considered a pass or a fail.

It takes the emotion and personal identity out of the experimentation process – a bad results doesn’t mean you’re a failure, it means you learned something valuable and can move to the next version of the test.

A good starting point is to design at least one test for each of the “Three Lenses of Innovation” –Desirability, Feasibility and Viability.

For Desirability, we might test our customer’s willingness to pay, or what messages get the highest click-through rates on an ad.

For Feasibility, we might test our capacity, how many customers we can realistically serve in a given period of time, or how well our products/services stack up against the competition.

For Viability, we might test our cost assumptions, or profitable each of our menu items will be at our current scale.

In terms of designing specific tests with specific outcomes, the best book is called Testing Business Ideas by Strategyzer.

It’s like a cookbook of 44 different experiments to suit different purposes, with clear instructions around ingredients, steps and what you should have by the end of the process.

This is a helpful starting point, and it’s better to run three honest tests than one big convoluted messy test.

If the result of the test won’t change your mind or your actions, it isn’t worth running…

Crunch points in the validation process

The point of an experiment is that it will shape your thinking.

If you run a test, and will proceed with your current plans no matter what, then it’s not a test, it’s an early iteration.

Don’t get us wrong, early iterations are good, but a test should lead you to take different types of action depending on the result.

e.g. if we can get 50 signups in the first month, then we’ll feel confident to…

If we get 10 signups in the first month, then we’ll try a different marketing tactic…

If we get 0 signups in the first month, then we’ll try another market…

These crunch points feel dramatic because they will change how you proceed.

A positive result might speed up your plans, a horrible result might send you back a few steps in the process, and a mixed result might make you re-run the test with a few adjustments.

Remember, it is not your job to MAKE the test work.

It’s your job to design a good test, to do good work, and then to run it a fairly and scientifically as possible.

Biasing the test or pretending a mixed result is a positive result will not serve you well.

A failed experiment is still an excellent use of your time and energy, if you can fail in a way that advances your work and saves your resources.

Entrepreneurs can be over-the-top, and sometimes that leads to big sweeping statements at a crunch point.

You probably already know this but it’s worth restating it anyway: no single test result can crush your dreams, end your business or boot you out of entrepreneurship altogether.

If that’s what you’re feeling, then it’s helpful to name the feeling as being real, but the situation is not that dire.

It’s highly likely that the early versions of your products, services and brand are not popular, won’t go viral and won’t be instantly lucrative.

That was never the point of these tests.

These tests are looking at potential, for early signs, for traces of desirability feasibility and viability.

Unless you’re doing something illegal, nobody except you can squash your business at the testing stage.

You might decide that you need to make the work better, or to commit to more marketing, or to do more groundwork before launching, but it’s not game over.

Accurate diagnosis and framing your reality

The best thing you can do after testing is to accurately name your situation.

This is helpful to do with an external person, be it a friend, industry peer, coach or advisor.

It helps you get the facts of your situation out of your head, into the light where they can be seen and not twisted into horrible self-criticisms.

e.g. “Customers hated it” vs “Customers liked some aspects” vs “We couldn’t reach our customers” vs “We’ve changed our perception of who our customers are”.

The best process we’ve found is called Facts vs Fake News.

Your partners makes a list with three columns called Facts, Fake News and Good Questions.

Facts are things like “we ran this experiment”, “we spoke to 20 people”, “we had 8 signups”, “we’ve made four rounds of changes” and “customers are appreciative of…”.

Fake news is more like “nobody will buy this”, “I need to start over”, “our competitors will just take over this space anyway” and “we can’t charge us much as…”.

You can see the difference already – both feel true in your head, but some have evidence and some are emotionally driven speculation.

Once you see the connections and differences between those two lists, we can start framing up good questions.

Rather than jumping to a conclusion, we create fair, solvable questions like:

When does it become safe to open a second location?

What if I ran a pilot, where I learned to use the tools and meet customers?

Can I find mentors/advisors who are doing similar work at a larger scale?

What if I recruit a manager and free myself up to go out and win more work?

Do I want to build this, or do I want to want to build this?

What if I raised my prices and people still thought it was good value?

This process is great for identifying limiting beliefs, and turning them into good questions rather than instant answers.

But not everything is a mindset issue, there’s often some alarming maths that needs specific action.

Again, this is made easier if we accurately frame the situation and see all of our options.

e.g. “we need to make more money” can be further broken down into

How might we grow the size of the market?

How might we increase our share of the market?

How might we raise our prices?

How might we raise the amount a customer buys at a time?

How might we increase our return frequency?

How might we design follow-up products and services?

How might we shrink our variable costs?

How might we reduce our overheads?

How might we lower our breakeven point?

The great this is that only one of these needs to improve to see more money flowing through our business.

If some of those sound impossible, that’s ok, there’s probably another 2-3 options that are do-able.

What Would Other Entrepreneurs Do?

As lovely and unique as you are, your situation is probably not THAT unique in the history of business.

There are so many other founders who have had the same challenges, constraints and opportunities as you, either in your field or in parallel fields, who you can learn from.

You can hear how they framed/reframed their problems, what they tried, what worked and what didn’t.

Their situation is not identical to yours, but their stories and strategies will give you lots of inspiration and options to consider.

How did they become more desirable?

What did they do to boost their capacity or improve the quality of their work?

What helped them improve their margins or their throughput?

How did they run tests?

Who gave them inspiration or good advice?

How did they bounce back from their own “Oh Shit” moments?

You can find these in interviews, business books, podcasts, courses, biographies or in a community of practice.

Sharing your numbers and assumptions

A good way to check the uniqueness of your situation is to share your numbers with people you trust.

As we mentioned earlier, this works because smart people often don’t know how to bring up issues and ideas out of the blue, but they’re good at responding to questions and situations that strike them as being unusual.

i.e. correcting you rather than offering advice upfront.

Bear in mind that everyone carries their own perspective and goals for a business in their field.

Some want to see a huge opportunity, some want to see a resilient company, and there’s merit in both worldviews.

What investors want to see

We’ve had several clients and colleagues go on Shark Tank.

Everyone says it was useful, and yet only one took the Shark’s money.

That’s because the aim is to be able to answer the Shark’s questions; pre-empting them and bringing evidence, to allay their fears very early on.

Even if you’re not looking for investment, it’s helpful to examine the big questions that investors use in assessing companies.

Here are some of the most common questions and green flags:

Is this a lucrative enough market? Can someone build a billion-dollar business here?

What’s your competitive advantage? Why are you meaningfully better or cheaper than the competition?

Why hasn’t this been done before? What’s different about this timing or this scenario?

Are your margins high enough? (What constitutes “enough” depends on your industry).

Can we see a path to profitability? If not today, will this be profitable for somebody in the future?

What size shock would it take to ruin us financially? What’s the smallest change that could lead to a catastrophe?

What experienced entrepreneurs care about

Founders have a different perspective, thinking about survival and flexibility rather than gunning for a billion-dollar valuation.

They might encourage you to ask questions like:

Can we lower the minimum order quantity?

Can we delay some expenses?

Can we offer incentives for further purchases from active customers?

Can we bring in systems that use less of your time in acquiring and serving customers?

What’s the next breakthrough for our industry and can we start experimenting with it today?

What assets will be valuable for you in the future, and can we buy/build them now?

The answer to those questions is actually secondary – the main aim right now is to be able to show them your numbers.

At least with a big envelope, you’re on the same page.

What to do next

When you encounter an “Oh Shit” moment, the best thing to do is to name it, feel it, and then break it down into smaller pieces.

This is easier with a second person as a sounding board, preferably someone impartial who wants you to succeed.

If it’s that you don’t know about the maths and terminology for your revenues, costs and margins, these are “figureoutable”, so long as you can identify the gaps in your knowledge and research them bit by bit.

If it’s that your forecasts are dauntingly large or alarmingly small, you can start experimenting with different assumptions to see how they change the viability of your business.

If it’s that you don’t know how long it takes to serve a customer or don’t know how your audience tends to shop, use a Test Card to design experiments that have clear conclusions.

If you don’t know what numbers to use, build an assumptions table to keep track of your guesses and research, so that the facts are separate from the total fabrications.

If it’s that everything feels overwhelming or doomed, build out a Facts vs Fake News list that separates evidence from your brain’s weird narratives.

If you don’t know what you don’t know, or don’t know if your guesses are fair, talk to other founders or advisors and show them your process.

Whatever you do, don’t rage-quit and don’t bury your head in the sand.

“Oh Shit” moments aren’t resolved by magic, but they are usually much easier to treat than you first realise.