Helpful Financial Concepts For Thinking About Growth

Growth is an enticing topic for pretty much every business, and yet the growth process is often full of unpleasant trade-offs and expensive risks.

When you’re thinking about growth, there are several concepts that give you helpful terminology for describing exciting options and dangerous traps.

By learning the language, you’ll be better equipped to have good discussions with your team, your investors and your accountant.

Here are a few more…

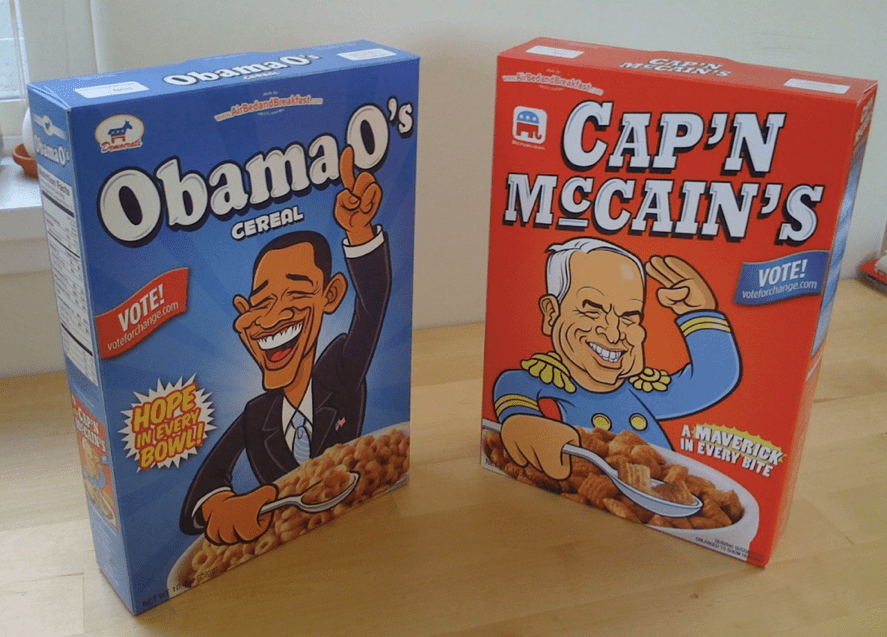

Do You Need An “Obama O”?

Obama O’s and Cap’n McCain’s were two brands of novelty cereal that were created and sold by Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, to help them get out of a financial pickle while they built their scrappy startup “Air Bed and Breakfast”.

At this point, their startup was based on the air mattress and Pop-Tarts they offered their house guests, and they saw huge potential to roll the concept out across an expensive city like San Francisco.

But they were also $40,000 in debt.

With the 2008 US election on the front of everyone’s minds, the founders launched the two cereal brands and sold them for $40 a box, generating a quick $30,000 in cereal income while the business took shape.

Interestingly, it was the cereal story and not the pitch that convinced Y-Combinator to accept Brian and Joe into the exclusive program.

What’s great about this story is how the urgency for revenue opened the founder’s minds to random income streams.

They didn’t let their egos get in the way, they got to printing cereal boxes and gluing them together, but they also didn’t pretend that they were becoming a cereal company.

The Obama O’s were limited and effective – exactly what was needed, without being a long term distraction.

Here are some guiding principles for Obama O opportunities:

Obama O’s Make Good Margins

What would be the point if they didn’t?

The aim is to generate a profit, so there needs to be a good margin between the value to the customer and the cost to deliver the product or service.

A $40 box of cereal isn’t really a cereal, it’s a talking point or a piece of art.

A $6 box of cereal wouldn’t have helped the founders very much.Obama O’s Respond To Existing Demand

In the original case, it was the interest in the 2008 election; the biggest topic in their country.

The founders weren’t looking to support either candidate or persuade voters, but rather make the most of the existing passion and support for both candidates.

You don’t need to make waves, you want to ride waves.Obama O’s Use Existing Assets

Assets are what enable a business to generate revenue, be they tangible assets like machines and factories, or intangible assets like skills and brands.

The founders used their existing talents to design the boxes, their connections to produce them cheaply, and their existing audience to drive demand.

Without these assets, there would not have been an opportunity.

When you look for your own equivalent, start by thinking about what assets you have today; transferrable skills, excess capacity, valuable talents, anything that gives you an unfair advantage over someone like me.Obama O’s Don’t Require Significant Commitment

Generally speaking, businesses make money by solving a problem in bulk, then charging customers individually.

The larger upfront commitment you make, the cheaper you can produce your product or service, like how a factory can produce a pie for less than you can in your kitchen.

For some industries, the only way to compete is to start at a large scale, and these industries aren’t right for an Obama O cash flow generator.

When money is tight, the last thing you want to be doing is tying it up in equipment, contracts or anything that won’t pay back its costs for several years.

You’re looking for something that can be built quickly and without an expensive setup.

Don’t buy a $5,000 camera to do a $600 photo shoot, better to borrow or rent one instead.Obama O’s Are Cash Flow Positive

Ideally you want something that lets you earn money before you spend money, such as anything that can be paid in advance.

This ensures that you’re not drawing down on already scarce funds, and can use your customer’s money to pay your suppliers.

The aim is to generate cash, so it’s better to make less overall profit in exchange for the certainty of not creating bad debts.Obama O’s Shouldn’t Conflict With Your Primary Brand

It’s ok to do something completely separate or abstract from your core business, customers might not even see the connection between the two.

What doesn’t work is when your little cash cow undermines your main brand, especially if it calls your integrity into question.

Don’t launch a low quality version of your product/service, and don’t launch a business that sits in conflict with the ethics or mission of your core business.

Bizarre spin-offs are charming to customers, so long as you do a good job of each of them.

Organic vs Inorganic Growth

You’re going to meet people with exciting sales pitches for how you can grow your company.

They’ll talk about investments, mergers, acquisition, paid marketing, and talk down about a term called “organic growth”.

They might be right, but it’s important to know the difference.

Organic growth means to grow naturally, following on from what you’re already doing.

e.g. word of mouth, more customers see your current marketing and eventually become interested, you find small tweaks and improvements in the business that slowly boost your sales.

These are usually cheap to implement and hard to rush.

Inorganic growth, the opposite approach, is where a business buys up another company, or spends a lot of money on paid ads to acquire more customers.

This drastically speeds up the process, giving you a larger customer base in a hurry, but you’re paying for it.

Organic growth comes from delivering on your promises, making it easy for new customers to find you and shop with you.

Inorganic growth comes from finding customers who aren’t necessarily looking at your business, and making a targeted pitch or taking over their accounts.

It’s the difference between growing an online audience by blogging versus growing through sponsored posts.

Or the difference between making Reels or TikToks that might get shared versus paying to appear on prospective users’ social feeds.

One is not better than the other.

Organic is cheaper and safer, but in some industries there’s no time for it – you need to make progress in a hurry or else competitors will swoop in.

e.g. Apple buys up other businesses and turns them into features for their existing products, rather than trying to invent these concepts from scratch.

There’s no guaranteed recipe for either approach, you can learn a lot from what others have done, but your unique circumstances mean that certain approaches are a bad fit for your circumstances.

If you’re building a startup, a competitor might look at you in the same way, offering to buy your business and upgrade their own company instantly.

This is worth considering as an exit strategy, and there are specific steps som startups take to become more desirable as an acquisition target.

Growing Like A Weed

People use the expression “growing like a weed” to describe sudden, unusually fast growth, and anyone who’s done any gardening understands the analogy.

Interestingly though, the way some weed killers (2,4-D herbicides if you’re wondering) work is to make the weeds grow faster, to the point that they can’t sustain themselves and die.

In other words, rampant growth can kill you, especially when you get bigger faster than you can increase your support systems.

Excited startups get impatient and try to seize their moment, and end up growing too quickly.

They raise money, hire new team members, and invest in large marketing campaigns.

But you can ramp up the customer facing side of your business much quicker than you can ramp up your team’s culture, training and leadership capacities, or faster than you can build proper customer support or engineering teams.

The growth that excited you can soon become the thing that kills the company.

Sunk Costs Can Keep You Small

The real danger in old financial models is in the sunk costs – things you’ve purchased in the past that aren’t particularly useful, but which have become comfortable.

These are dangerous because they tempt you into spending more money than necessary, raising the number of sales required to break even.

In return, you get to avoid the awkward process of “cutting your losses”.

Common sunk costs include homemade websites, products that make no margin, subscriptions you don’t use, marketing collateral with outdated information, staff with specialisations that are no longer relevant, or even worse, staff members who are awful to work with.

A good example of how to analyse sunk costs comes from Dave Ramsey.

Imagine you’ve previously spent $18,000 on a motorbike, but haven’t gone for a ride in two years.

You keep it, because it’s not worth anywhere near what you paid for it, and you like having it around.

Here are the two important questions:

1. How much would it sell for today on eBay? (Let’s pretend $6,000)

2. If you had $6,000 cash in your hand but no motorbike, would you rush out to buy this second-hand bike?

You know the answer in your gut.

90% of the time, you would rather have $6,000 of cash, and wouldn’t go seeking out any sort of motorbike.

Right now, you have these sunk costs in your business – things that if you didn’t currently own them, you wouldn’t run out and buy.

By making the brave call to cut them now, you drastically drop your overheads/startup costs, and therefore boost your profits.

Life is too short and business is too hard to spend money on things that don’t make your life better.

Donations and Sustainability

If you’re an organisation that takes donations, it’s worth re-running your calculations without that extra help.

For example, if you are a charity that runs a business (possibly a social enterprise), you’ll want to know what surplus/loss was made in the business itself, and then what surplus/loss was made including donations/grants.

e.g. we made $35,000 surplus but had $60,000 of donations.

It’s important that your business works as a business.

A café should not lose money.

A retail store should not lose money.

A community housing organisation should not lose money.

These core businesses should be able to pull their own weight and cover their own costs.

If they can’t, then something is fundamentally wrong, and you have a limited runway to fix it.

Donations do not solve these problems, they buy time and potentially hide the real issues.

For this reason, it’s important to list the core business performance as well as the overall performance.

Semi Fixed Costs & Inflection Points

Some of your expenses kick in at odd times.

You might be able to have one staff member serve up to 20 clients, but when you hit 21 clients you need a second person.

The same goes for equipment, administrative support, bandwidth or customer service.

Whilst your revenues gradually get bigger, your costs hit points where you suddenly have to spend money to expand your capacity.

These are called Semi Fixed Costs, and you’ll want to identify the trigger points for expansion.

That way, when you forecast an increase in customers or revenues, you also remember to increase your forecasted expenses, since you’ll be growing your operations.

You need to have an opinion on when these moments could come up in your business, as it determines how you’ll approach investment.

Some types of business can “bootstrap” and self-fund their own growth, whereas others need outside investment to go through these inflection points.

Investors love buying into a business that is already doing well, but they also hesitate to rush a deal.

If you see the need for investment, start building familiarity with funders before it’s urgent.

Should we go for Variable or Fixed Costs?

The nice part of variable costs is that you only spend money while you make money.

If there are no sales, you don’t burn your cash on unused resources (like staff time, utilities or space hire).

You literally pay for what you use, so these costs can be predicted as percentages, rather than definitive dollar amounts.

They’re also associated with costs that aren’t your speciality.

e.g. you don’t want to pick specific web pages to advertise on, so you use Google Adwords and pay per person who clicks on your ad.

There are cheaper ways to do each of these, but they’re far more time consuming.

A lot of people would rather just pay for what they use, and not worry about saving a few dollars in exchange for some big headaches.

If you’re starting a new business, you’ll have less financial pressure and wastage by turning fixed costs into variable costs.

On the other hand, things are cheaper when you buy in bulk.

If you know that you’ll be consistently using a person/item/service, it’s probably cheaper to buy it outright.

e.g. hiring an accountant or lawyer rather than paying their expensive day rates, or leasing an office rather than paying weekly co-working fees.

Renting is more expensive than owning – in the long run – and it provides more flexibility.

If you know what you’re doing, you’ll get more value for money by turning variable costs into fixed costs.

This is a hard call because it’s not purely a maths question – it requires you to assess risk, the likelihood of selling out, and the impact of sales being lower than anticipated.

You get to decide if/when to convert variable costs into fixed costs, but our suggestions are:

To wait until the variable cost options annoy you (e.g. not having enough customisation).

To wait until your volumes increase and the savings entice you.

To learn what you do/don’t like by outsourcing to specialists at first.

Time Value of Money

Would you rather have $100 today, or $100 in five years time?

That’s probably an easy answer.

Would you rather have $100 today or $200 in five years time?

Maybe a bit less easy.

Would you rather have $100 today or $120 in a year from now?

These questions are interesting because we know that money today is more valuable than the same amount in the future, but it’s tricky to pinpoint when that changes.

$100 today is better than $100 in five years, because we can put it in the bank and turn it into $140 by then, and inflation will reduce the buying power of $100 in the future.

This affects you, because an investor is more excited at the prospect of your business making $100k of profit this year than they are if you make $100k profit in five years time.

That future money is worth more like $60k today to an investor.

People will want to analyse your “Net Present Value”, which helps them determine if the money they invest today will pay off enough in the future.

Let’s not look at that equation right now, but the key detail is that future money is worth less than today’s money, and investors will have strong opinions about how much you need to make to justify their investment.

Risk-Adjusted Returns

Some new founders might ask “how much is a good return on investment?”, which is a surprisingly murky question to answer.

The answer isn’t 5% or 10% or 15%, it’s “it depends on how risky the investment is”.

If two offers, let’s say a term deposit and a cryptocurrency, both offer you a 7% return on your money, which would you choose?

Everyone would pick the term deposit, as it has way less risk.

So an investor has several different options for their money:

Put it in the bank and earn 2%

Lock it away in the bank and earn 5%

Put it in index funds, earn 9-12% but the value might also go down

Put it into an established venture and earn 15%

Put it into an exciting, high risk business and earn 40% and also maybe lose most of that money

That’s why 11% isn’t “good” or “bad”, it depends on how much risk you have to take to get that level of return.

Investors, rightly or wrongly, want to be compensated for taking more risk by potentially receiving a higher rate of return.

Don’t Get Bitten By Your “Jaws”

Back in a former role at ANZ bank, senior managers would often track the company’s performance by the “Jaws”.

This is a graph made up of two squiggly lines, one shows the growth in revenue and the other shows growth in expenses.

Hopefully, your revenue is growing faster than your expenses, or at least keeping pace.

These two lines get further apart or closer together, like a top and bottom jaw.

As that jaw closes, your business gets bitten – costs growing faster than income is an early sign of trouble.

You might still be making a good amount of money, but over time the negative growth will erode your margins.

There were probably 100 different metrics we could have focused on, but for a bank this was the one that mattered.

Maybe it’s a good one for your dashboard?

Growth is good, at the right pace with the right goals and in the right proportion.

These concepts give you language and the ability to spot potential headaches in advance, usually when spirits are high and the future feels exciting.

The point of growth is that it gives you more profit, more stability and more freedom.

If your projections show that growth will cause more stress, more risk and more obligation, it might be time to rethink your goals and your model.