Origin Stories - Prompt Pack

We’ve previously discussed the power and usefulness of writing a clear Origin Story.

Your story is powerful because it gives you:

A renewed sense of who you are, why you’re doing this and how far you’ve come

A reminder of why you’re a good person to build something unique and remarkable – if it wasn’t worthy of remark, you wouldn’t be building it

Both a logical and emotional reason why this business needs to exist

Clarity on the DNA of your brand, with vivid examples instead of generic corporate jargon

A story you’re proud to tell, that helps people understand and appreciate your work, and which they can share with others

Some guidance for future decision making, keeping your next steps consistent with why you started this in the first place

A source of fuel and direction when you’re feeling flat or lost in the future

Something that will attract and resonate with your next best hires/funders/partners

One of the only advantages a startup has over a giant corporate rival – authenticity

Inspiration and material for your brand positioning and brand identity

Different length introductions to pitches, panels and public speaking

That’s a lot of good reasons why you need to write yours out, but it doesn’t make it easy.

Fortunately, this prompt pack will help you identify the golden elements that already exist in your story, and will give you a little bit of structure without feeling like a bland formula.

Like gold, they might be buried under a bit of dirt and require some refinement before it becomes treasure.

First, we’ll get out our metal detectors to see where we should go digging…

Identifying Components Of Your Story

There are no strict rules, but the cliches of storytelling are cliches because they work over and over again.

Audiences love certain details, and the aim here is to keep the audience’s interest, not to write the most chronologically accurate autobiography.

Don’t lie, don’t exaggerate, but also feel free to skip to the most interesting/relevant details, and people can ask questions later.

Your job right now is to identify the hidden gold in your story, then dig it up.

We can clean, melt, cast and polish it later, we just need it out of the ground.

Who are the key people in the story?

You, your team, friends, family, advisors?

Maybe even some early customers?

What are some of the key moments that have happened?

Maybe you earned a qualification or got a job in the industry?

Did you feel a growing entrepreneurial itch?

Did you leave a job?

How did you find and serve your first customer?

Have there been failures and setbacks?

What have been your biggest wins?

What surprised you?

Where does your fuel come from?

What drives you forward?

What makes you angry?

What makes you optimistic?

What’s helped you find your direction?

How did you make tricky choices?

How do you know what to aim for?

Do you have a “muse” who’s inspired you to make something?

When did you spot an opportunity?

Was it through a job or a friend?

Did you encounter a great potential customer?

Did you see a chance to raise/acquire some funds?

Have you pivoted because you saw a chance to make a better type of business?

Where have you encountered adversity?

Was it external or internal?

What was difficult?

When have you stopped or nearly stopped?

When have you had “Lightbulb Moments”?

When have you changed your mind?

Did it help you make a tough trade-off decision?

Did you feel inspired to make a new product/service?

What happened next?

Who have been your biggest supporters?

Is it your core team?

Friends and family?

Customers?

Funders?

Peers in this or other industries?

When has their support been most useful?

Who have been your rivals?

Have you encountered passionate and capable competitors?

Or even underwhelming/incompetent competitors?

Who disagrees with the premise of your vision?

Who agrees with the premise of your vision but goes about it in a different way?

What have these rivals inspired you to do?

What have been the biggest milestones along the way so far?

Could it be in the setup of your business?

Could it be in generating some momentum and some revenue?

Have you had many compliments, recognition or awards?

Which milestones felt the most meaningful to you, even if no one else knows about them (e.g. getting 1,000 subscribers to your newsletter)?

What principles and values are important to you and your business?

Where have these surfaced?

Where have you made a call that might have surprised other people?

What traditions do you not care for and which corners will you happily cut?

What habits/behaviours do you uphold because they are important to you, even if others are relaxed about them?

This should give you a heap of scribbled notes, half-formed ideas and a messy collection of examples/explanations.

Next, we’re going describe our cast of characters…

Naming & Introducing Characters

A story becomes more compelling if we care about the characters.

That means they have to be:

Easily understood

Likeable or unlikeable

With clear motivations

If the characters are bland or vague, the audience won’t form a mental picture, nor care about what happens to them.

Sometimes we want to describe them in a sentence, and sometimes we want to show examples of their behaviour/success/preferences.

It’s helpful to think about both.

What would this person have on their business card?

How might they fit that stereotype, and how might they surprise you?

What have they done in the past?

Have they gone above or beyond?

How did you first encounter them? What was your first impression?

What did this person want from you?

What is their most likeable/redeeming feature?

What’s their least likeable/worst feature?

Should I be using their first name, full name or photo? (it probably depends on the setting and whether or not you’re about to praise or condemn them)

Of course, you won’t be using 70% of that detail in any one scenario, but it helps you think about a well-rounded and memorable description of the person, their context and their intentions.

Now it’s time to find the key moments where your story takes important turns, for better and for worse…

Moments & Decisions

“Books don't change people; paragraphs do, sometimes even sentences.”

- John Piper

It’s hard to capture years of work and slow change in a story, so instead we want to focus on turning points.

These are the moments and decisions where you started, pivoted, doubled down or quit.

There’s usually some emotion behind the choice, and they are often the “first domino” that then sets up the next changes and generates momentum.

Yours are probably unique, and they might not stand out as key moments to you right now.

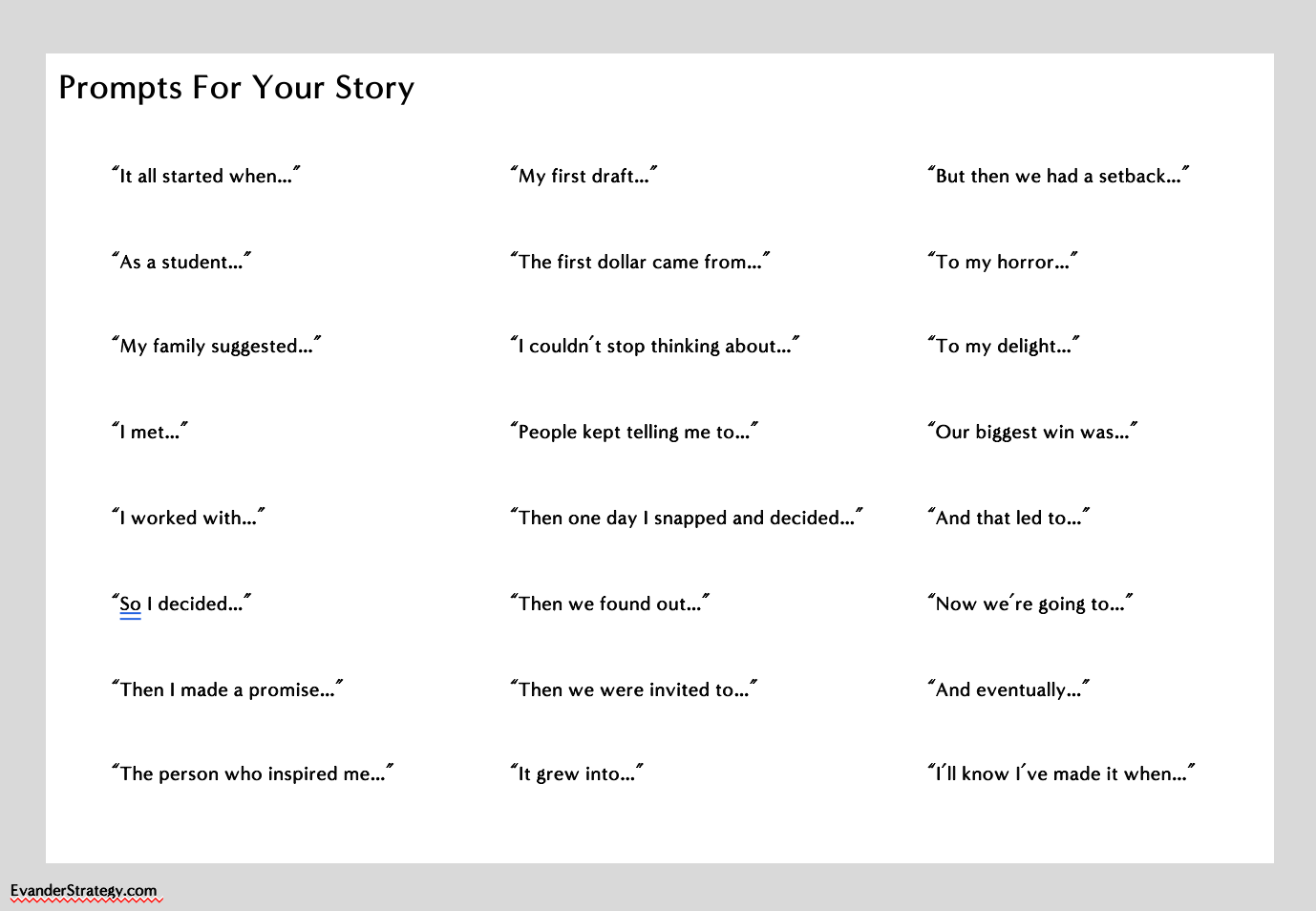

Here are some prompts for you to complete, let’s see what they spark in your memories:

“It all started when…”

“As a student…”

“My family suggested…”

“I met…”

“I worked with…”

“So I decided…”

“Then I made a promise…”

“The person who inspired me…”

“My first draft…”

“The first dollar came from…”

“I couldn’t stop thinking about…”

“People kept telling me to…”

“Then one day I snapped, and decided…”

“Then we found out…”

“Then we were invited to…”

“It grew into…”

“But then we had a setback…”

“To my horror…”

“To my delight…”

“Our biggest win was…”

“And that led to…”

“Now we’re going to…”

“And eventually…”

“I’ll know I’ve made it when…”

Please don’t try to cram all of those into one story, but you can take 6-10 of them and have a helpful starting structure that won’t be boring.

Next up, we plot it on a timeline…

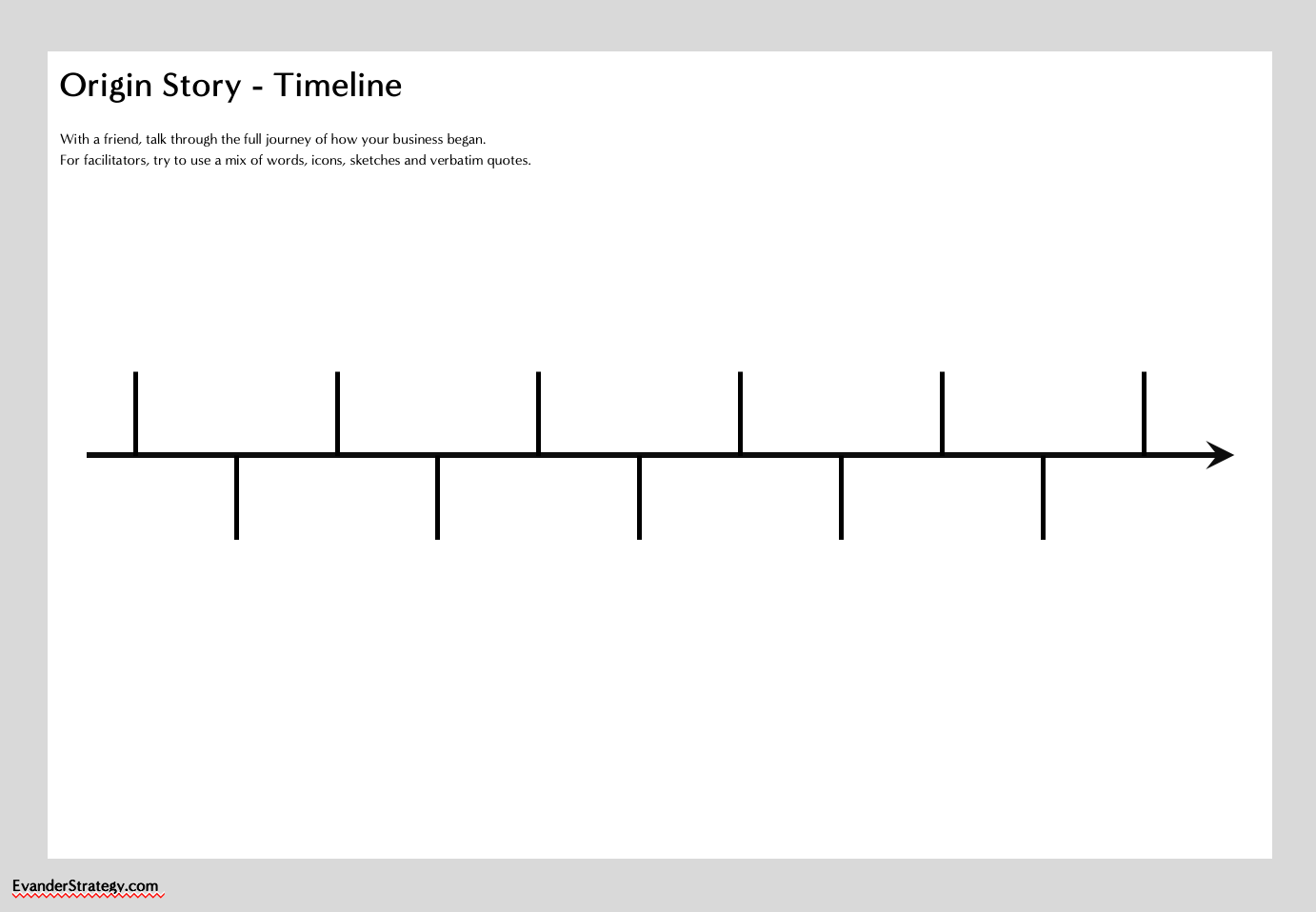

Drawing The Timeline

It’s helpful to visually plot the story, for two reasons.

Firstly, it reminds you of some of the less memorable but still influential events and work that led to the highlights.

That way you don’t look like an overnight success.

Secondly, it gives us the full history, which we can then use to pick out certain elements and themes to suit different occasions.

It’s easier to write it this way, rather than trying to start with a short version that you have to expand in the future.

Different facilitators have different ways of drawing this up, the easiest one to plot out is a straight timeline across the middle of a board/page.

Then we start from the start, alternating above/below the line mainly to save space.

Not every year needs an equal amount of space, but each 3-6 months usually deserves some sort of comment.

We can always make the line longer or rearrange text later.

Most people like to start with the facts, the irrefutable history of what happened at what time, and that’s fine.

The role of a facilitator is to do the drawing for you, and then add three things:

Icons, giving a thematic sense of the following words

Sketches, drawing people and key moments

Quotes, a few bold words that explain an era or big decision

This is great detail, but it’s not vivid enough for an audience and hard for someone to read in a hurry.

Let’s create a plan for pacing out the right “beats” of the story

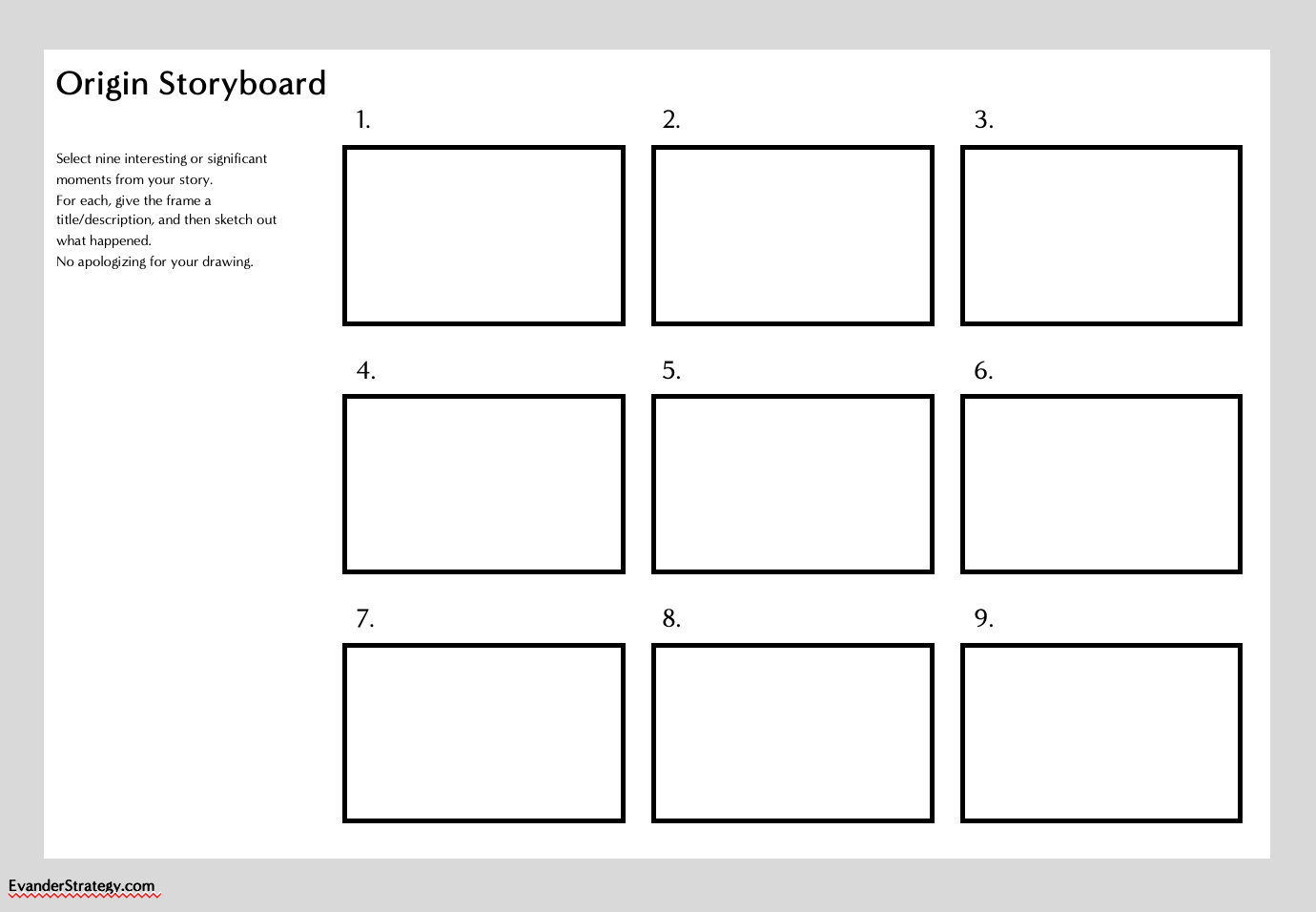

Origin Storyboards

Your story can expand and shrink to suit different occasions, like an elevator pitch, a Shark Tank pitch, a TED talk or a keynote presentation.

We can use the prompt above to create a structure, taking 9-10 of those starting points and assembling a skeleton.

As a starting point, you can try to explain five phases of your story, with two points or ideas in each:

The beginning and the backstory – you, your scenario, your motivations

Exploring and your first steps – who you met, what you learned, what you liked/hated

Building and progress – what you started, what you prototyped, who you served, what worked/failed, iterations and pivots

Deciding and where you’re up to today – what you’re going to create, the momentum you have today, line in the sand moments, signs that this is the right path for you

Forecasting the future – what’s next, what you need, how you can knock over the next dominos, what you hope for the future

Despite what you might tell yourself, you probably have interesting points in each of these categories.

We’ll frame these up as a storyboard, taking 1-2 points from each phase, or maybe 3 for the beginning, 3 for the middle and 3 for the end.

A storyboard is where you draw or describe a key moment, making it easy for the audience to visualise.

This storyboard does not need to be beautiful, it doesn’t matter if you don’t rate your own drawing skills, what matters is that you’ve picked NINE INTERESTING DETAILS.

If they are well drawn and not interesting, it hasn’t worked.

If they are rough and keep the audience hooked, it’s working.

This looks great, so now it’s time to try it out…

Practicing Your Story

Founders sometimes expect that their next version of the story will now be permanent, and then get fixated on keeping the same wording, pacing and details.

That’s not what we’re going to do.

The point of the story is that it is yours, it is true and it is flexible.

If you’re trying to remember someone else’s phrasing, it won’t sound persuasive or natural.

If it’s not the truth, you’ll find it hard to remember.

If it’s not flexible, it won’t feel like it suits each scenario and setting that you’re in.

Instead, try it out 10 times, in 10 different ways, to see what you like to tell and to see how different audiences respond.

What captures their attention?

What makes their eyes glaze over?

What makes them laugh?

What prompts a question?

Which questions show interest and which show a misunderstanding?

Did the story land well?

This works because you’ll experiment with changing the length, terminology and emphasis on certain aspects.

e.g. the way you tell it to your hairdresser might be different to how you’d tell it to an investment banker, and probably for the best.

After 10 times, you’ll naturally come up with an 11th version, with strengths from lots of practice, issues ironed out, and even new aspects that weren’t in the first 10.

The story is going to evolve, and it should evolve.

There is so much to talk about, so don’t be afraid to include alternate details and examples, so long as they’re all true and you’re happy for it to be shared.

It will also change when your future hires tell it – it becomes legend, with blurred details and exaggerations, so your job is to ensure it doesn’t veer into misrepresentation.

Final Suggestions

We’re really keen to not make this a “fill in the blanks” format, but rather a series of options that you can arrange to suit your own style.

Here are some other tips for creating a story that you’re proud of:

Trey Parker, the creator of South Park, tells writers to try and link the bits of their stories with words like “therefore” or “but”, rather than “and then”.

This creates some tension and interest for the audience, rather than just a meandering sequence of events.

Cause and effect, people love that.Don’t be afraid to pause a draft and start again from a different angle.

It’s a good use of time.Using AI for this would be like using AI to write your wedding vows or a love letter.

It’s so personal and contextual to your unique set of circumstances, how could AI possibly know all that happened?Only use words you’d already use in conversation at a dinner party.

You don’t need buzzwords or slang, only swear if you’d already swear in front of people, don’t use academic phrases that never come up in normal life.

If some important terminology needs explanation, build in the explanation.Feel free to be honest and vulnerable, but check “would I say this on a crowded train?”.

You won’t always want to recount intensely emotional moments, that becomes draining and desensitizing, go with what feels like you.People are allowed to not get it and not understand the significance of some points.

That’s fine.

If everyone doesn’t get it, then something might need an adjustment or more explanation.

You can download a copy of these templates and prompts here.