Evander Strategy’s Customer Interview Crash Course

“Innovation is hard because ‘solving problems people didn't know they had’and ‘building something no one needs’ look identical at first.”

- Aaron Levie

If you are designing a new business, the best piece of advice you’ll hear is “go and talk to your customers”.

You should talk to them, but you want to do it in the right way, or else it can send you down the wrong path.

Every single person who learns this approach ends up saying “I’m really glad I did that”, but it is confronting.

It would be easier to send a survey link, or to read data trends instead.

Do you fill in surveys honestly, or at all?

And that’s why we need to get the truth, straight from our customers.

It will make you a better designer and better entrepreneur, because you’ll be hyper-clear on who you’re designing for, how they behave, and what they truly care about.

We don’t even need to build up to a punchline in this guide, here’s the short version:

People are liars when you ask them about their preferences and what they might do in the future, but they’re honest about what they’ve done/chosen in the past.

You need to meet your customers to truly understand them and you shouldn’t want to outsource this process.

There is an easy and mostly painless way of conducting these conversations, if you use the right questions and make it feel natural.

Some of your assumptions are going to be disproven, and that’s incredibly valuable for you.

These core ideas might seem new, but they consistently prove themselves to be true in the real world.

The process we’re recommending will break the work into small steps, helping you have better conversations and getting golden customer insights.

It can help you earn more money or save a tonne of money, probably both.

We’ll look at who to interview, what to ask, what to listen for, and most importantly, how to decide that this whole process is in your best interests.

Let’s get started…

The need for honest validation

“We must learn what customers really want, not what they say they want or what we think they should want.”

– Eric Ries

Validation is your friend.

As a business owner, the most important person to convince that this is a good idea is YOU.

You don’t need to persuade or trick an investor, you need to prove the idea’s worth to yourself, and that gives you an incentive to take the validation process seriously.

And yet, new entrepreneurs are almost never excited about the validation process.

They either see it as a waste of time as everything is already perfect, or see it as confronting, the bearer of bad news.

That “bad news” is actually a blessing – full of early warning signs that you’re looking at a tough or non-existent market, or that customers care about something you didn’t anticipate, or that there’s a bigger opportunity adjacent to your current idea.

There’s a lot that needs to be validated, and most fall into three big categories:

Desirability – is there a market, what do they care about, how will we reach them?

Feasibility – what assets do we need to own, what do we need to do, and who can we work with in order to delight our customers?

Viability – how much will we be able to earn, how much will we need to spend, and does the business make a good margin?

The hard part is that we need all three to go right in order to succeed – two out of three isn’t enough.

If it’s not Desirable, then sales become painful and revenue will be slow.

If it’s not Feasible, we burn our customers and our team.

If it’s not Viable, it will run out of money, gradually or suddenly.

Having said that, the first one to work on is probably Desirability, and that’s all about customers and their needs.

We can’t invent a customer out of thin air, and we can’t force people to buy something.

Instead, we can observe real customers, understand their motivations, and then check if certain wants/needs are important to them.

That’s by far the most important piece of validation.

If there are no customers, or they are not motivated to try/buy something new, then this is not the place to build your new business.

That might be painful to hear, but it’s better to hear it now rather than once you’ve made a huge investment.

The best book about customer validation is The Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick.

It’s essential reading in Evander Strategy’s programs, we ask all founders to read at least the first five chapters.

This guide has some specific tips and quotes from the book, but we usually read the opening paragraphs in our workshops to give you a sense of Rob’s core idea:

“Trying to learn from customer conversations is like excavating a delicate archaeological site. The truth is down there somewhere, but it’s fragile. While each blow with your shovel gets you closer to the truth, you’re liable to smash it into a million little pieces if you use too blunt an instrument.

I see a lot of teams using a bulldozer and crate of dynamite for their excavation. They are, in one way or another, forcing people to say something nice about their business. They use heavy-handed questions like “do you think it’s a good idea” and shatter their prize.

At the other end of the spectrum, some founders are using a toothbrush to unearth a city, flinching away from digging deep and finding out whether anything of value is actually buried down there.

We want to find the truth of how to make our business succeed. We need to dig for it—and dig deep—but every question we ask carries the very real possibility of biasing the person we’re talking to and rendering the whole exercise pointless. It happens more than you’d ever imagine.

The truth is our goal and questions are our tools. But we must learn to wield them. It’s delicate work. And well worth learning. There’s treasure below.”

Why focus on customers?

"I regard the hunt for new clients as a sport… if you play it grimly, you will die of ulcers. If you play it with lighthearted gusto, you will survive your failures without losing sleep. Play to win, but enjoy the fun."

- David Ogilvy

The best people to ask about a market are customers themselves.

Firstly, if we can’t find them in order to talk to them, we have a huge problem.

It’s hard, but shouldn’t be THAT hard to find customers.

Customers are out there somewhere, naturally congregating and looking at potential solutions.

If you can’t find anyone to interview, why would they be a good customer base for a business?

It might be that you need to move out of your comfort zone to meet with them.

We call this “going fishing where the fish are”.

There’s not much point casting your hook and bait into the water if there are no fish around, even if it’s a convenient place to spend time.

We want to know that there’s a deep pool of motivated customers, or else your startup will quickly run out of people to sell to.

Proving that a population exists is not the same as proving that a market exists.

If there are lots of people who fit your target customer profile, but they mostly seem to be content with what they’ve got, then this might not be evidence that there’s a lucrative opportunity.

We can describe customer pains in three levels:

Vitamins – these are nice to have, but are not urgent and sometimes hard to tell if they’re working

Painkillers – these are important and time sensitive, customers will take action to find a resolution

Oxygen – these are crucial and urgent, with customers desperate for a resolution (but these can become invisible when you have them).

Our suggestion is to understand where there are customers with Painkiller level needs.

Vitamins are too flimsy, customers often forget their needs/interest.

Oxygen problems are not all that common, and can rarely be addressed by new startups.

Painkillers are a nice middle point, where customers are motivated and will end up choosing something, be it you or your competitors in the future.

While customers might tell us about a market, they can’t tell us too much about what to invent or how it should be sold.

They can only tell us about themselves and their perspectives…

What can customers genuinely tell us

"Many marketers confuse listening to their customers with just asking them what they want. It’s not the same. Don’t ask your customers what they *think* they’ll do.

Observe them and ask them about what they’ve *actually* done.

Behaviours > Opinions."

- Katelyn Bourgoin

When we talk about customers, we are talking about the person/people who have an interest or need, who makes a decision, and who pay you.

This may or may not be the same as the “End User”, who ends up with your products, or the “Beneficiary”, who benefits from the results of your work.

e.g. a parent buying a child a bike for Christmas is the customer, but probably won’t end up riding the bike themselves.

The travel co-ordinator in a large company chooses hotels and airlines for their teams, even if they never need to pay a visit.

A project manager decides on what software their company should use, then rolls it out to hundreds or thousands of their colleagues.

That’s why we want to understand the power dynamics, thought process and true motives of our customers.

There are usually two reasons behind a decision, the good one and the real one.

These real reasons might not be very nice to say out loud.

People would rather tell you they chose their new car because of its fuel efficiency, generous warranty and reduced emissions, rather than “I reckon this will help my love life” or “I want to impress/keep up with my friends”.

We like to think that we are rational and sensible buyers, but in reality we tend to make emotional decisions, then search for rational reasons to support our preferences.

This is not a criticism, it’s our job to see the situation as it is.

Customers won’t tell you this straight away, you’re going to have to deduce it or work your way up to those questions.

What they will tell you are the facts of their past behaviour.

So if you think back to when you last bought/researched a car, we might ask you about:

What you typed into Google, or who you went to for advice, or where you started your search.

Did you start with a few brands in mind, or a set of parameters on a website?

Did you skip all of that and just buy your grandma’s old car because it was cheap or you wanted to do her a favour?

What questions did you ask, and how did you narrow down your options?

When you say it out loud, the chances are that you made some funny decisions along the way – like setting totally arbitrary rules around price and features, or ruled out certain car companies for petty reasons – and that’s great!

We want to understand those petty-yet-powerful reasons that led to them taking action, that’s where the gold is.

Lots of customers will end up choosing something different next time, but their thought process and rationale will likely remain very similar.

Not every story is helpful though, we only want to hear from real customers who ended up buying something.

If they bailed on the process part way through, or if they’ve never researched buying something like this in the past, they are not going to be your startup’s early customer.

That means their opinions and preferences are likely to give you a false reading.

They might be unenthusiastic and not end up being a customer for anyone in your category, so their criticisms aren’t dealbreakers.

Or they might sound very enthusiastic and full of compliments, but when it comes to making a purchase, something gets in the way, or the benefits don’t outweigh the costs.

We once had this at a former startup – a new hire sent a survey to our mailing list, and was telling us about our feedback.

“We sent the survey to 724 people, and 24 filled it in”.

That’s the first alarm bell – our list aren’t engaged with our emails.

“Of those 24, 16 of them haven’t been to any of our events, workshops or programs”.

Alarm bell two!

When asked about who gave which response, they said “No, all responses are anonymised”.

That’s alarm bell three, the data from the eight past customers is now totally mixed in with the people who have stood on the sidelines.

So now we have the illusion of data, but it’s actually a complete mess.

It’s hiding the real stories.

When we asked “why did those 16 people fill in the survey if they’ve never been to any of our stuff?”, we got to the real reason – because we offered a prize of Gold Class movie tickets.

Now, this might sound undemocratic but it’s the truth – not all feedback is equally valuable.

If the numbers said “70% of respondents rated us highly”, we miss the truth of “how many of our current/past customers rate us highly, and why?”

The specific complaints or suggestions from past customers could give us amazing insights for the future, but they’re lost in the vague compliments from random people wanting to win some nice movie tickets.

Customers can tell you:

Here’s who I am

Here’s what we bought in the past

Here’s how we went about buying it

Here’s what was most important last time

Customers can’t tell you:

What they would buy if they were actually your customer

Embarrassing truths like “I’d never spend money on that” or “I bought this for a very selfish reason”

What you should sell

Why is this hard and vital for founders

“I think of problems as gold mines. The world's biggest problems are the world's greatest opportunities.”

- Peter Diamandis

These conversations are full of gold, but like gold nature, it’s surrounded by dirt.

You are going to be dealing with a lot of mixed feedback and surprising responses, which you can then process and break down in order to reveal those shiny golden insights.

That’s why this is confronting – because customer interviews will frequently be full of seemingly “bad” news.

Perhaps customers aren’t as enthusiastic as you thought, or they care about something else, or the way they make decisions is hard to influence, or the decision makers are hard to reach.

But that’s not really “bad” news if you hear it early.

It can encourage you to pivot, and target either a different market or a different problem, or it can encourage you to persevere, because there are good customers out there who you are learning how to reach.

It’s bad if you stick your fingers in your ears and spend lots of money on developing and launching your dream product, in hopes that once you launch, a new horde of customers will magically appear and form a line outside your door.

When we were working with a coffee company in the South Pacific, we’d asked the founder about his customers and why they chose this brand in particular.

Straight away he proudly listed off the top three reasons.

Cafes, restaurants and hotels stocked this coffee because of its good quality, because it is local, and because it has a good story attached.

We asked if we could talk to these customers, to hear from them directly.

When asked about why they are loyal to this particular brand, those venues all had a surprising answer, which we can summarise as:

“We stick with this one because the sales representative cleans our coffee machine”.

What?

“Well, no one on our team really knows how to service the machine, but the salesperson from the coffee company does it when they’re here, so we’re never leaving!”.

The founder was stunned, and even a bit horrified.

They didn’t know this was happening.

But what a gift – now they know what to promote when approaching new stockists, and which parts of their offering to never cut.

This work needs to be done by your team, not your intern.

The insights from customers are sometimes hidden in body language, pauses, and throwaway remarks.

You need to be there to pick up on these, to read between the lines, and to ask good clarifying questions.

Reading someone else’s abridged notes of a conversation is nowhere near as valuable.

New founders love to complain that this is inefficient, but veteran founders agree: if you don’t yet have a strong customer base, customer interviews are a great use of your time.

The essentials - what constitutes a good interview

“The questions to ask are about your customers’ lives: their problems, cares, constraints, and goals. You humbly and honestly gather as much information about them as you can and then take your own visionary leap to a solution. Once you’ve taken the leap, you confirm that it’s correct (and refine it) through Commitment & Advancement.

It boils down to this: you aren’t allowed to tell them what their problem is, and in return, they aren’t allowed to tell you what to build. They own the problem, you own the solution.”

- Rob Fitzpatrick

In our workshops, we have a rule called “Don’t be Pierre”, named after a founder who conducted a very misguided interview with the rest of our cohort.

Pierre had all the ingredients for a valuable customer discovery session – he wanted to trial and market a traditional Eastern European probiotic drink, which had few competitors in stores and strong health benefits.

The problem was how he conducted his conversation.

He had a batch of homemade probiotic drink, and then forced the group to try some.

When people asked questions like “hey man, what’s this?” and “where’s it from?” and “what does it do?”, Pierre gave short dismissive answers like “Ah, don’t worry about that, just try it, it’s good yeah?.

When people said “I dunno man, tastes kinda weird”, Pierre would say “No it doesn’t!” and hand a cup to the next hostage.

He was leaving so much gold on the ground, out of pride and overconfidence.

The group’s questions were a gift – a sign of what his brand will need to answer and a chance to practice how he can put people’s minds at ease.

The unusual taste could be a chance to talk about “yes, that’s because it is unique…” or “that’s because of it’s signature health benefits…”.

If he’d have had a dialogue with his audience, he could have told the drink’s interesting history in different ways, to see which versions make a customer’s eyes light up.

He could have asked them about what sort of health drinks or probiotics they’d tried in the past, and what they did/didn’t like about them.

And that’s what a lot of founders do – they squash a good opportunity by trying to secure agreement, rather than by having a genuinely interested conversation.

There are a lot of ways to run a bad interview, but good interviews tend to have three things in common, which are know as “The Mom Test”:

Talk about their life instead of your idea.

Ask about specifics in the past instead of generics or opinions about the future.

Talk less and listen more.

“It’s called The Mom Test because it leads to questions that even your mom can’t lie to you about. When you do it right, they won’t even know you have an idea.”

This is excellent advice, it’s hard to go wrong when you start with these three principles.

The bulk of the design can be done in advance of the conversation – by selecting who you should talk to and what sort of prompts can get them talking about themselves.

If you work on a short list of helpful questions, you can then let the conversation run freely, without a clipboard or survey form that feels overly formal.

You can let people tell their story, go down the rabbit hole with them, asking genuine and curious questions along the way – that’s where you tend to find gold nuggets.

You are not pitching anything.

You are not asking for feedback on your business idea.

You are not asking for product suggestions.

You are not asking for a sale (although we might return to these people later).

A good interview can be a few minutes long, it doesn’t need an introduction or a conclusion, nor does it need an appointment.

You can go to a conference or trade show and have ten great interviews in an afternoon, rather than weeks of trying to book in calls over the phone.

But most importantly, a good interview is one that is with a potential customer.

If they’re not a potential customer, then their opinion is unhelpful.

Good and bad questions

"Asking the right dumb question is often the smartest thing you can do."

- Alex Blumberg

Good questions get people talking about themselves, their past behaviour, and their wants/needs.

These might start with:

Can you tell me about a time when…

When that happened, what did you do next…

What other options did you look at?

How did you decide what to go with?

Who pays for it?

How do you feel about it now?

You might notice that a lot of these require follow up questions, which will happen naturally if you’re engaged in the conversation.

Bad questions are when we search for validation by leading the customer into agreeing with our assumptions:

Would you buy a product that did…

Would you pay $99 for…

What do you think of our idea…

Would you buy this?

How important is…(without giving them a polite way of saying “not important at all”)

Interestingly, the bad questions boost your chances of getting exciting confirmation, but that’s not the goal.

The goal is the truth.

If you have to twist people’s arms to hear confirmation, this might be a sign that this is the wrong audience, or the wrong problem to be working on.

A good interview doesn’t need a lot of questions, it just needs well-designed questions.

A questions is well designed when it is meaningful for confirming/invalidating your crucial assumptions.

What to listen for

“Most entrepreneurship is differentiating between ‘good-sounding dumb ideas’ and ‘dumb-sounding good ideas’.”

– Aaron Gotwalt

There are several valuable signals that we can pick up on:

Stories of a real customer trying to solve this problem or follow their interest in the past.

Examples of what the customer has paid, what they received and how happy they were with what they got.

Signs of preferences, how they manage trade-offs, drawcards that entice them and dealbreakers that rule an option out.

Examples of how they went about their research, whose opinions or recommendations helped them, and how they narrowed their options.

Evidence of them putting their money where their mouth is, taking a next step or furthering a relationship.

These are great because they show us that this person is a genuine customer, who has a real need/interest, how they make decisions, and how we can know that they are not just being polite.

The opposite of these can also be helpful negative signals, like never following up on a potential purchase, quitting when it gets hard, not being the decision maker, or them not being willing to take a next step.

e.g. you thank them for their time, send them a link to something they claimed to be excited to read, then seeing if they ever click on it.

This helps us separate courtesy from real interest.

What counts as evidence

“Practically everyone I’ve seen talk to customers (including myself) has been giving themselves bad information. You probably are too. Bad data gives us false negatives (thinking the idea is dead when it’s not) and—more dangerously—false positives (convincing yourself you’re right when you’re not).”

- Rob Fitzpatrick

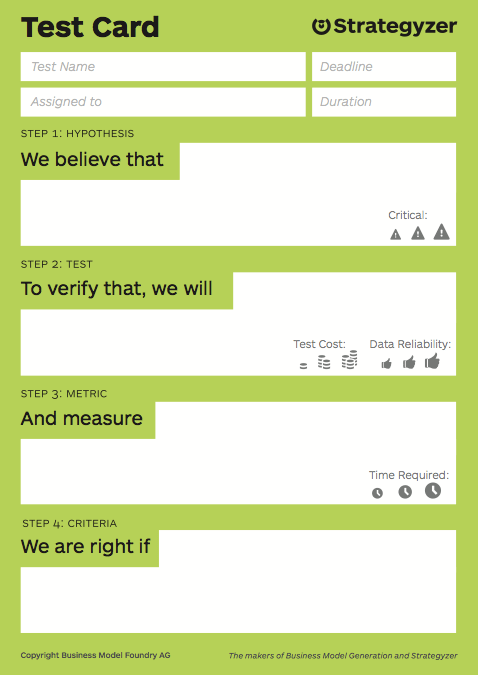

One of the best tools for designing experiments is called The Test Card, made up of four prompts:

We believe that…

To verify that, we will…

And measure…

We are right if…

Founders HATE these, but/because they are incredibly valuable in sharpening your thinking.

These four prompts help you replace flimsy outcomes with concrete evidence.

So instead of “yeah most people seemed to like the idea”, we’d end up with “we spoke to 20 café owners, offered them a free trial when our prototype products are ready, and six of the twenty have signed up”.

These cards nudge us to design tests that are specific, that check a crucial assumption, that are measurable, and that have a pass/fail line.

Compliments and faint praise don’t count.

Verbal commitments don’t count.

Enthusiasm from non-customers doesn’t count.

Vibe doesn’t count.

The way to draft these tests is to ask “What would prove this concept to someone dispassionate? What would they need to see in order to believe our core assumptions are reasonable?”

It will be different for your stage/industry, so you get to decide on what constitutes enough of a positive signal.

This will help you determine the minimum number of customer interviews, and what level/type of enthusiasm counts as a “win” for the experiment.

As a guide though, it should be something measurable that a motivated customer would be happy to give you, not something unreasonable.

i.e. setting up a time for you to meet their team, joining a waiting list, making a pre-order, agreeing to a second conversation, accepting a discount/special offer for their first purchase.

We don’t want to sweeten the offer too much, just enough to make it an easy “yes”, but not as strong as those Gold Class movie tickets that skewed our earlier survey.

So in the example above, you might decide “Well if we are approaching 20 café owners and only one signed up, we’d see that as a fail, but six would definitely be a win, so we’ll set the line at 3 out of 20. If we can’t get 3 out of 20 to agree to a free trial, something needs to change and we’ll try again”.

That way the test has a clear deadline and a meaningful result, no matter what it may be.

Designing a test

“We go through the futile process of asking for opinions and fishing for compliments because we crave approval. We want to believe that the support and sign-off of someone we respect means our venture will succeed. But really, that person’s opinion doesn’t matter. They have no idea if the business is going to work. Only the market knows.

Learning that your beliefs are wrong is frustrating, but it’s progress. It’s bringing you ever closer to the truth of a real problem and a good market. The worst thing you can do is ignore the bad news while searching for some tiny grain of validation to celebrate. You want the truth, not a gold star.”

- Rob Fitzpatrick

There are lots of ways you can test an idea, depending on your stage and your industry, lots of which involve customer conversations.

Sometimes these need quick informal conversations, like The Mom Test, and sometimes you need more of a framework or gimmick.

The best book for inspiration is Testing Business Ideas by Strategyzer, which is like a cookbook with 44 recipes for tests.

Some test Desirability, Feasibility or Viability, or a combination.

Some validate if there is a customer and a pain point, some are for early prototypes, and some are for generating early sales.

Some use a bit of technology, some use simple bits of paper or even just a conversation.

The way to use the book is to flick through the 44 different recipes.

90% of them will be irrelevant, but 10% could work for your scenario, giving you 4-5 good options to follow.

For each of them, follow the process properly – you’re not allowed to half-bake it or cut corners then complain that the recipe sucks.

This is a great task to check with a coach, advisor or sounding board, especially with people who have run tests and experiments before.

They will help check your thinking, make creative suggestions, and offer suggestions of what should constitute a pass or fail.

You should ask yourself “If this test comes back with a positive confirmation, what will we do? If this test comes back as a fail, what will we do?”.

This needs to be decided in advance.

If the honest answer is “I’m just going to go ahead with my plan anyway”, you can skip the pretence of this process.

Be a good scientist.

You’re welcome to make tweaks, try different variations and persevere with your vision, that’s a good thing.

But don’t pretend a fail is a pass, you only end up fooling yourself.

Conducting conversations

“Everyone is interesting. If you're ever bored in a conversation, the problem is with you, not the other person."

- Matt Mullenweg

The most crucial starting point for your conversations is knowing where your customers are.

Assuming they do exist, where are they spending their time?

Where do they congregate and what do they talk about?

What sites or groups do they frequent?

What events might they attend?

These meeting points are known as “watering holes”, like the parts of a desert or jungle where animals visit throughout the week.

This is where you can most easily strike up a conversation, without it feeling creepy or out of place.

If you wanted to ask about running shoes, the gym or a run club might be a good watering hole.

A chat can start as simply as “I was looking for new shoes, how are the Hokas?”, and most people will be happy to give you a decent answer.

If you wanted to ask about sauces and dressings, the supermarket might be a good watering hole.

A chat can start as simply as “Oh I need a barbecue sauce, have you had that one before?”.

But it might be weird to randomly ask people at the gym about sauces, or people in the supermarket about running shoes.

You don’t need an introduction or a backstory, it’s easier to start with a compliment or an honest question.

You’re not doing a sales pitch, and you definitely don’t want the other person to feel like you’re selling something.

You also don’t need a camera or notepad for a short conversation.

The purpose of initial chats is to see if this person is representative of a customer base, and if they’re going to be good to talk to.

If someone is rude, shy or awkward, it’s not your responsibility to change them or push through a difficult chat.

Our number one tip is incredibly simple, requires no talent and makes every part of this process easier.

Ready?

Be genuinely interested in your field.

If you’re genuinely interested in customers, the industry, the product, what people enjoy, what’s overrated and underrated, what trends are picking up, then all of this becomes almost easy.

After a while you can do these interviews for any topic or field, but you’ll be even better in areas where you have a real curiosity and established knowledge.

We’re not saying “pretend to be genuinely interested”, that’s exhausting.

We’re saying be genuinely interested, or go and work on a different problem/market.

Objections to this process

"Cheating on customer discovery interviews is like cheating in your parachute packing class."

- Steve Blank

Right now you might be feeling some resistance forming.

It usually hides behind a sensible reason, but deep down it’s driven by discomfort.

And to be clear, this process is uncomfortable, especially at first.

It involves potential rejection, potentially having your ideas disproven, and potentially means changing direction.

Here are some common objections:

“Look, customers don’t know about this now, but if everyone would just swap to our approach, we’d be able to…”

Tumblr user squareallworthy said it best:

“If your solution to some problem relies on ‘If everyone would just…’ then you do not have a solution. Everyone is not going to just. At not time in the history of the universe has everyone just, and they’re not going to start now.”

People do not magically change their behaviour, it comes from incentives and changed conditions.

You cannot force anyone into anything in modern entrepreneurship, you can only nudge people into taking their own best interests.

“We already know what customers want…”

This is tempting to believe because it’s true-ish.

You probably know what some customers want in a similar situation.

If you’re still correct, this process will be easy, quick and reassuring.

In reality, you’re likely in for a small surprise, and it’s better to get this now than when you’re fully invested in not-quite-the-right-thing.

“This will take too long…”

If you’re near your customers, this will take hardly any time at all.

What takes a bit of time is finding your customers, crafting questions, creating formalities to boost your confidence, stalling because you’re nervous, etc.

We are not describing an academic research project, it’s a series of short, well-designed conversations with the right audience.

“I can’t find twenty customers to talk to…”

We’ve literally heard this from companies who have just told us that they’ll onboard 2,000 customers in a few months.

If you can’t find twenty people, and you magically assume you’ll soon be in front of thousands of soon-to-be-raving fans, what does that suggest?

“Let’s just use Surveymonkey…”

The temptation is that this is more scalable and efficient.

Two questions should knock this one on the head:

How many survey requests do you genuinely respond to?

How honest are you in answering their questions?

We tend to rip through these questions, which are often poorly designed and lack all evidence or context behind why you gave a certain answer.

Ten good customer interviews are better than 100 lazy survey responses.

“It makes me nervous, I don’t do things like…”

This is true, but it’s not a reason to not do it.

Can you think of any successful business owner who is too afraid to talk to their customers?

Neither can we.

This process can be adjusted to be as easy or natural for you as you like.

You don’t need to be an extrovert or socially charming, so long as you are very polite and genuinely interested in the topic you’re asking about.

And the real one: “I don’t want to do something that might mean we need to take a backwards step…”

Ding ding ding!

This is the biggest objection – founders and project managers who don’t want to risk “going back to the drawing board”.

In some ways, you appreciate their honesty, but ultimately this does not serve their interests.

If there’s a problem, when do you want to find out?

If you need to take a few backwards steps or make a pivot in order to thrive, isn’t that a good thing?

Rob Fitzpatrick sums it up beautifully:

“You need to search out the world-rocking scary questions you’ve been unintentionally shrinking from. The best way to find them is with thought experiments. Imagine that the company has failed and ask why that happened. Then imagine it as a huge success and ask what had to be true to get there. Find ways to learn about those critical pieces.

You can tell it’s an important question when its answer could completely change (or disprove) your business. If you get an unexpected answer to a question and it doesn’t affect what you’re doing, it wasn’t a terribly important question to begin with.

Every time you talk to someone, you should be asking at least one question which has the potential to destroy your currently imagined business.”

Tips for introverts

“A person’s success in life can usually be measured by the number of uncomfortable conversations he or she is willing to have.”

- Tim Ferriss

This whole process probably sounds horrible if you’re an introvert.

Fortunately, it’s actually a difficult 20 seconds followed by a relatively straightforward conversation.

There are a few ways of making it easier through planning and getting out of your own head:

Design a test that you’d happily suggest someone else should run for their own business, that way you know you’re being fair in your expectations.

Decide that you’re not here to sell anything, but that you’re happy to make good recommendations to anyone who is interested.

Go in pairs, it’s much easier to have a lead person asking questions and a second person asking for clarifications. It’s really hard to be a good interviewer, note taker and perceptive listener at the same time. You also get the benefit of having someone to debrief with after the conversations.

Script a few different opening and closing lines that don’t feel awkward, that way you know how to start and end the chat.

Aim for a certain number of these conversations per day, starting with a small number. Don’t try this for the first time doing 40 of them at a conference.

Write out your questions on your phone, to look at before a conversation rather than in the middle of their responses.

Small incentives are a nice way to thank people for their time, but don’t go too large or you’ll attract people who aren’t actually representative of your market. We clearly don’t recommend Gold Class movie tickets.

Reward yourself for the attempt, not the end result.

Rob Fitzpatrick agrees:

“Pre-planning your big questions makes it a lot easier to ask questions which pass The Mom Test and aren’t biasing. It also makes it easier to face the questions that hurt. When we go through an unplanned conversation, we tend to focus on trivial stuff that keeps the conversation comfortable. Instead, decide on the tough questions in a calm environment with your team.”

Processing feedback - good, bad and mixed

"Never give up as an entrepreneur or innovator, but remember that it’s OK to give up on an idea when there’s nothing there or the markets not ready."

- Alexander Osterwalder

One of the most critical parts of the process is in how you process what you heard.

As a general rule, decide that you won’t leap to any conclusions on the day – no despair, no champagne.

As The School Of Life suggest:

"3am alone in bed is perhaps not the optimal moment at which to derive a true picture of reality. Wait - always - for the perspective of dawn"

No singular customer conversation should confirm or refute your core assumptions, we are looking for trends and signs of a deep pool of customers.

People will praise you and people would misunderstand you, and they’re both a bit wrong.

People will give you ideas, but they are not the founder of your business.

People make sweeping statements that they haven’t fully thought through.

We can come back to these people, particularly those who seemed enthusiastic or signed up to hear more from you in the future.

In a later conversation, you can show them your pretotypes, prototypes or let them use your Minimum Viable Product, but please don’t mention all of that in your first chats.

What to do next

"You can't expect to hit the jackpot if you don't put a few nickels in the machine."

- Flip Wilson

The point of this crash course is to encourage you to take imperfect action.

That means reviewing these steps and applying them to a decent standard, but not dawdling on the sidelines while you try to craft the perfect interview question.

Not overconfident, not timid.

Here are five steps you can take today:

Decide that you genuinely want to talk to customers

Find where your customers naturally congregate, and go there (physically or digitally)

Decide on how many people you need to talk to, what you’ll ask, what you’ll measure and what constitutes evidence that your assumptions are correct

Ask good, open questions in the style of The Mom Test

Record what people tell you, and whether they show signs of real interest

Eventually this is going to help you design products and services for your customers, but don’t start on that now.

The main thing here is to gain insight into customers and their wants/needs, your ideas aren’t on the table yet.

The three books we’d recommend are:

The Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick

Obviously Awesome by April Dunford

Testing Business Ideas by Strategyzer

For more advice on interviews, have a look at:

How To Conduct User Interviews by The Interaction Design Foundation

The d.school Empathy Fieldguide by Stanford d.school

Techniques For Empathy Interviews In Design Thinking by Envato

If you’d like a PDF version of this guide for you and your team, you can download it here.