Crunch Point: Product-Solution Fit

Once we know who our customers are and what they want, we need to work out how to serve them well.

In a lot of cases, customers don’t particularly understand the details of what you do, they focus on how it gives them what they truly care about.

They care about solutions, and solutions come from products.

This is what that famous Henry Ford quote is about, where he suggested hks future car customers would ask for “a faster horse”.

They’re not passionate about innovation, they just want better results.

Technology changes faster than people do.

A customer’s desire for entertainment has been solved in a different way every generation.

The ways of entertaining the masses have changed drastically, even though people aren’t necessarily very different from a century ago.

If you were in Rome 2,000 years ago, you’d probably have loved going to the Coliseum to watch a spectacle.

So for the entrepreneur, the challenge becomes “how might we give customers what they want, how much of it should be familiar and how much should be new?”

This is hard because, as Rory Sutherland says, “the opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea”.

Some people (like Peter Thiel in Zero to One) believe that innovation comes from a 10x improvement over the competition.

Then people like Virgil Abloh suggest that a 3% difference is enough of a change to be meaningful innovation.

Both are correct.

There are examples where companies succeeded by niching and specialising, and other examples where companies succeeded by diversifying and collaborating.

Some entrepreneurs found it helpful to make new products more affordable and democratic, others had more luck through premium pricing and exclusivity.

Some customers love a high-tech product, some love simplicity and minimalism.

More importantly, innovation is measured from the customer’s perspective.

You probably don’t know anyone who saw an internet-connected smart fridge and rushed out to buy one, even if it is a new proposition.

But you probably know a lot of people in the mid 2000’s who saw the iPod as a breakthrough and an object of desire, even though there were several other superior MP3 players already available.

We all have brands that we cannot understand and may treat cynically, and brands we like that other people might dismiss or deride.

As long as the customer says “wow, this might be for me!”, it counts as a meaningful innovation.

All of this starts with developing a genuine understanding of the customer and their perceived problems.

If we don’t know what they care about, then the hard parts of innovation get even harder.

This is a field of logic and emotion – a better product might have nothing to do with technical superiority.

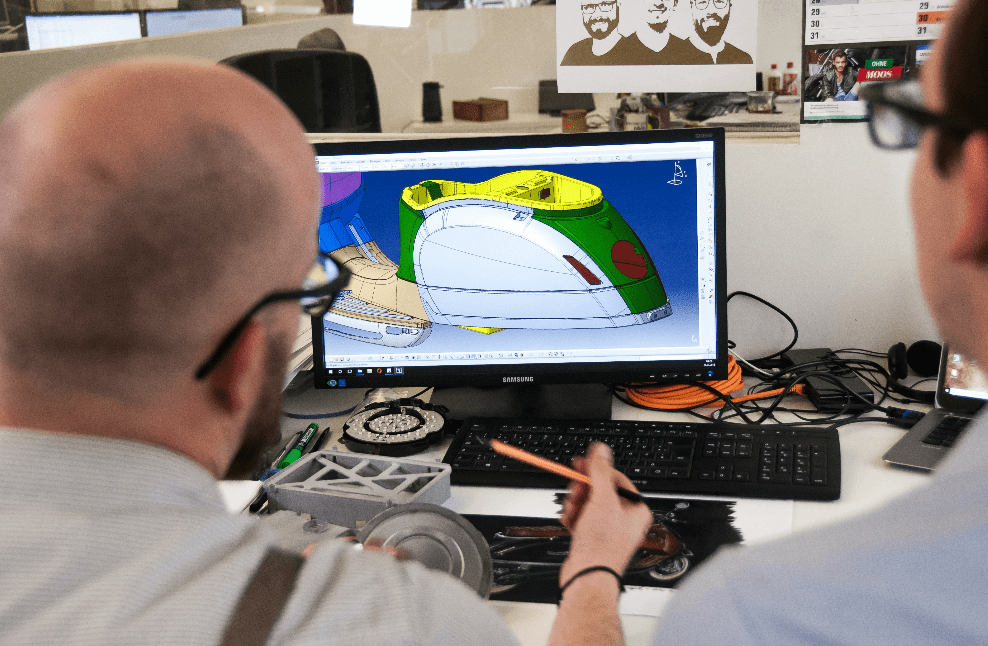

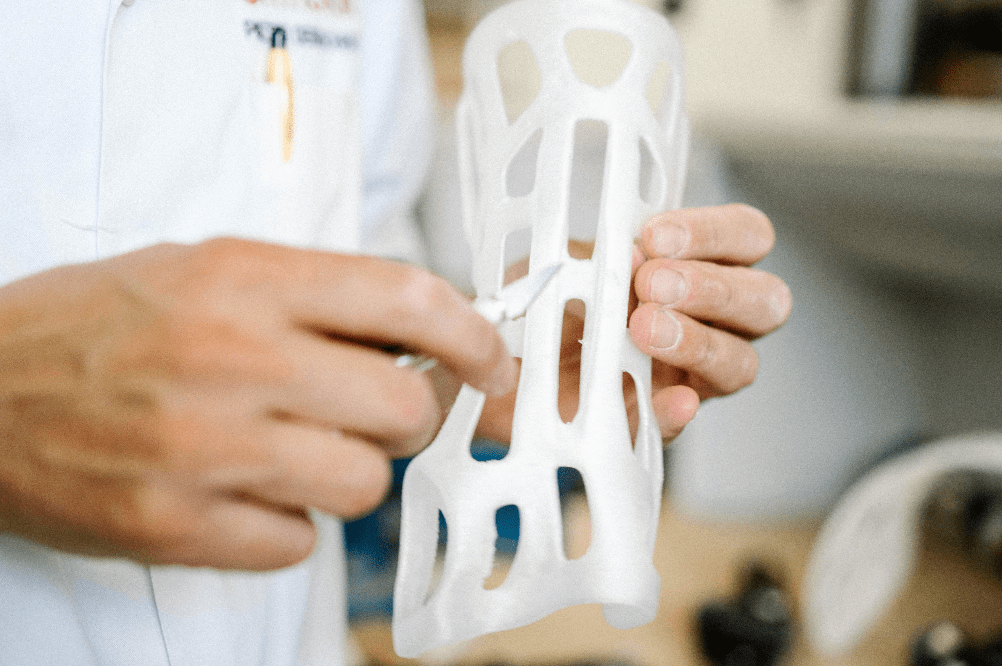

And that’s why this is a process, full of experimentation and iteration.

It’s hard to forecast because there are so many ways it could go, and we’re likely in for a surprise…

What counts as a product?

When we describe different types of products, we are really saying “things you can sell to a customer”.

That sounds imprecise, but the key elements are that:

1. You are involved in the value chain

2. It is going to a customer

3. It is connected to a revenue stream.

i.e. if you were trying to eliminate single-use plastic water bottles, the option of “just get everyone to not buy them” isn’t a product, whereas water in a can, refillable bottles and water fountains in public spaces all meet the criteria.

A product can be something that you make, something that you re-sell, but preferably not something you can be excluded from selling in the future.

After all, we want this to be a sustainable business.

Here are some common examples of product categories that might suit your situation:

Physical and digital products

e.g. Rolex selling watches, Audible selling audiobooks, IKEA selling flat-pack furniture, Canva offers intuitive graphic design tools.Physical and digital services

e.g. Lawnmowing companies trimming your grass, accountants prepare your tax return, insurers offer “cyber insurance” to businesses.Experiences

e.g. Musicians and promoters host concerts and festivals, tour companies take you on birdwatching tours, sports bars host Superbowl parties.Access to a shared resource

e.g. OpenAI gives you access to powerful AI models, gyms let you use a collection of high quality exercise equipment, Airbnb lets you book other people’s houses and apartments, streaming services let you access their library of content.Communities

e.g. Industry associations offer memberships with perks, discounts, events and promotions, Discord servers host a space for fans and peers to connect with each other.

As you can see, there’s overlap between them, but product no longer means “something that you can buy off a shelf”.

In a lot of cases, companies have moved away from physical product ownership, a mixed blessing for the consumer.

These products might be:

Inventions – something totally new and original

Adaptions – something that works in one format or location that is then adjusted to suit a new setting

Combinations – taking elements of several previously understood concepts and merging them together.

Iterations – an existing category of product, made better/differently to suit a new customer base

White labelled – something made by someone else, with your branding added right at the end

Partnerships and collaborations – taking the strengths (hopefully) of two brands to create a different product with a unique appeal

Remember, the majority of customers are not looking for the highest performing or objectively best product.

They are looking for the option that helps them the most or costs the least, and they’re often willing to compromise on some surprising aspects in order to get an outcome that best serves their own interests.

What counts as a solution?

A solution is when a customer breathes a sigh of relief, as they have resolved their search and can focus on something else.

This is not always permanent – sometimes the problem continues to come back, or customers enjoy finding new solutions, and those can be lucrative for you too.

If it doesn’t please them enough, they won’t buy from you once or again.

If their needs change, they’ll be back in the market soon.

Uber does not own or sell cars, they connect riders and drivers to solve the problem of getting from A to B.

Microsoft no longer sell software on CDs for you to own, they sell ongoing subscriptions to companies who want to avoid all forms of risk.

Spotify lets you access a nearly infinite array of music, podcast and audiobook.

In each example, these solutions have given the customer something they want, and with a downside.

Uber brought in surge pricing, Microsoft brought in Teams, Spotify underpays artists.

And yet customers are happy enough, until a better solution inevitably comes along.

Right now we’re seeing a lot of larger companies trying to excitedly (or fearfully) shove AI products onto customers in the hope that these are solutions.

But how many people do you know who are excited to use these?

Do customers genuinely have a need for an AI-integrated product?

Does this matter to them?

Or is this the result or corporate FOMO and the desire to be a leader in a lucrative field.

Customers choose solutions for a variety of reasons, some rational and some not.

You can think about several different philosophies when designing your own:

A technical solution to a technical problem

Not everything needs to be deep or emotional.

Sometimes your printer runs out of paper, so you buy more paper.

Sometimes you need a petrol station, and you fill up your tank.

Sometimes you need to fly to a different city, so you book a ticket.

Where it gets trickier is when the customer has choice, and needs to find a way forward.

That’s where brand preference and loyalty come in, to break the deadlock and to shrink the pool of options down to a manageable size.

Support with handling an adaptive challenge

Unlike technical problems which require a technical solution, adaptive challenges often can’t be solved with a single purchase.

e.g. no longer needing to own a printer, switching to an electric car and learning where/when to recharge on a road trip, hosting a digital conference so that people don’t need to fly interstate/overseas.

All of these require new behaviours, new thinking and a bit of discomfort.

But in each case, handling the adaptive challenge can greatly benefit the customer, the environment, and the people around us.

Sometimes a solution is something that helps guide, comfort or support the customer through these challenges – like how Duolingo nudges you to keep up your language lessons or how WHOOP encourages you to improve your exercise and sleep patterns.

They can’t do the work for you, but they can increase the odds of you keeping up your new habits.

Something that sparks joy

In some cases, customers aren’t looking for “good enough”, they want something that makes them smile.

Nobody needs a Nintendo Switch 2 or a Labubu on their bag.

Nobody needs an official baby-sized soccer jersey.

Nobody needs Tiffany charms or a Gucci belt.

And yet, customers always seem to find a way of acquiring what they believe will spark joy, even if it means buying a fake or cutting corners in other parts of their spending.

Joy is irrational, it often can’t be created in a lab from a recipe.

This is where the customer is always right – in matters of taste.

People can spot things they like, even if there’s no logic behind why, and will go to great lengths to get a good feeling.

The minimum effective dose

When we look for solutions, some people would argue that “anything above the minimum effective dose is waste”.

e.g. why take 2 painkillers when one will do they same job?

Why buy a Dyson Airwrap when a $40 curler will be good enough for the three times a year you need it?

For software, this is where customers will ask if they really need all the premium features, or if they really need everyone on the team to have a seat on the platform.

There’s a lot of money to be saved by sticking to the smallest amount needed to create the desired result.

When people complain that “with all these streaming services, we’ve just re-created cable TV!”, they forget that they can now opt in for only the content they want to watch.

It doesn’t suit everyone, but a lot of customers are happier with 4x $15 services than 1x $100 bundle.

A brand customers like associating with

Sometimes a customer is really picking a brand, then looking at an array of solutions/products later on.

e.g. you want an accessory from a new brand, then choose between a cap, shirt or phone case, as opposed to going hat shopping and seeing which brands come up.

In these cases, need has little to do with it.

The customer decides on what affiliations resonate with them, and then make “rational” choices and purchases.

Maybe they are averse to certain brands because of past negative associations – you don’t want to hear from a company because you associate them with an unlikeable person.

This is why a lot of startup brands first create an aesthetic and brand voice that customers are drawn to, then create merchandise and menu items later on.

How will we know when we have a “fit”?

It’s not like you have a “good ideas tap” and a “bad ideas tap” in your head, it’s just the one “ideas tap”.

We want to run the tap, and filter the ideas out later.

That’s why there aren’t too many rules when it comes to designing solutions, but some stringent criteria for determining if a solution is good enough:

“Dogfooding”

This lovely euphemism is when a founder, figuratively and occasionally literally, eats their own brand of dog food.

Perhaps it’s to test for quality, perhaps it’s because it’s cheap, but it shows the team and the market that you believe in what you’re selling.

If you’re selling a tech product, you and your team use the tech product.

If it’s a garment, you wear it day in, day out.

If it’s an experience, you act like your customer and walk in their shoes.

This shows you what a customer would experience, and will likely highlight areas of friction, confusion and dissatisfaction.

Users try it in a blind experiment

Pepsi used to run a little game at events called “the Pepsi challenge”, where triallists were invited to sip two little cups of cola from covered-up cans – Pepsi and Coke.

You’d drink one then the other, saying which option you preferred.

Of course, Pepsi knew that most people would pick the Pepsi cup, or else this would be the world’s worst marketing campaign.

Triallists were usually surprised to see which can they preferred, as they associated Coca Cola as being the tastier brand.

The same principle applies here – showing customers a few options without bias or pre-conceived opinions, trying them all, and asking them to rank their preferences.

This is good for working out if a product is better than the competition, then price becomes another factor, but you can test it as well.

The killer detail here is to offer a choice of prizes as a thank you – one generic (like a gift card or some chocolates) and one of your product.

Will they choose the one they claimed they liked the most?

Customers show signs of commitment and advancement

This is the number one signal to look for – when customers interact with our ideas, offers and prototypes, do they want to keep using them?

In the book The Mom Test, Rob Fitzpatrick talks about commitment (signing up for something, paying a deposit, asking to buy the prototype) and advancement (setting up another meeting, agreeing on a next step, introducing you to another customer).

These are so much more honest than kind words and compliments.

They are signs that a customer wants to progress with a transaction, out of their self-interest rather than to spare your feelings.

Pre-Sales

People vote with their wallet, and so any form of pre-sales will give you a strong indication of genuine demand.

If you can get 100 or 1,000 customers to pay a deposit or agree to sign up at a particular price, this gives you and your funders confidence that the solution looks to be good enough to your customers.

This is one of the earliest signs of Product-Market Fit, where customers show you that not only does the product work, it works well enough that they want to buy it.

What do we ask next?

Your situation is probably still quite murky, so here are some clarifying questions that will help you decide on some next steps:

If you feel like you have Product-Solution Fit:

Do we have good examples of different types of customer, to understand what they look for and how they choose/evaluate solutions?

How might we use our existing customer’s words to better advertise the strengths of our products to other prospective customers?

What are these customers asking for someone to build? What concepts or ideas make them say “shut up and take my money”?

What is the “expiration date” for your research? Is the market largely the same as it was 18 months ago? Even 6 months ago?

If you’re not sure if you have Product-Solution Fit, or are still running tests:

What would convince me that this is a good solution?

How much better are our ideas than what customers already have?

Are we too early or too late in the market?

Are we looking for new triallists or persuading existing buyers to switch to us?

What would I need to see to feel a strong yes or a tentative yes?

What would I need to see to feel a strong no or a tentative no?

What would give me a conclusive result?

Do customers show a willingness and ability to pay? One out of the two is not enough, unfortunately.

Realistically, have I done the work to see who’s out there and what they care about?

If you suspect that you don’t have Product-Solution Fit:

Am I relieved or disappointed? A bit of both?

Could someone else build a great business here? Would other entrepreneurs see this as a good opportunity, or a money pit?

What does this insight now allow us to do?

What are options B and C? What adjacent options might we explore now, perhaps for comparison?

How might I incentivise myself to be a good scientist? If I can’t celebrate a win, can I at least celebrate good work?

Remember, this work is never finished, it just becomes due.

We want to build products and offers that are great or good enough, but not necessarily flawless.

Product-Solution is a moving target, as customers, technology and competitors are constantly evolving.

These questions and methodologies need to become part of your year, not something you focus on once every five years.

You’re committing to the process of being a good designer, and that means being empathetic, creative, willing to be wrong and willing to change your mind.

But a lot of your biggest competitors have probably stopped focusing on the customer’s needs, and that’s your advantage as a startup – to pay the most attention to what sort of products actually matter to your audience.