Finding Business Opportunities

Entrepreneurs solve problems for customers, and social entrepreneurs solve meaningful problems for customers and beneficiaries.

The best way to do that is to design something that people are excited to buy, and that’s not always easy or obvious.

Rather than twisting arms or guilting customers into a sale, what if we had an offer that people would rave about and come back for more?

What if we had something truly desirable, something that was genuinely better than what’s available today?

How much could we do with a business like that?

This is a real opportunity, but it takes time, creativity and some failures along the way.

Once we’ve thought about our cause and motivation, then explored the Problem Tree and its roots, we can start to spot gaps in the market that could use a new business.

Those are the three tests;

· Is this work meaningful to us?

· Will this actually make a difference?

· Is there room for a good business here?

And while you get to name your cause and what is meaningful to you, the market will decide if they care about your new business.

For that reason, you’ll want to become an incredible listener, designer and salesperson.

Starting With The End In Mind

There is no perfect methodology for finding a business opportunity, but there are great checkpoints at the start and the end of the process.

Let’s start with the end – your business idea should pass three tests:

1. You have a customer who has a problem/desire/motivation.

We call this “Customer-Problem Fit”.

2. You have a product that solves the customer’s problem or gives them what they’re looking for.

We call this “Product-Solution Fit”.

3. Your customers recognise that your products/services give them what they’re looking for, and they’re happy to shop with you.

We call this “Product-Market Fit”.

These are tremendously important, because if your idea doesn’t pass one or more of the tests, it will be like pushing a boulder up a hill.

If you don’t have Customer-Problem Fit, your target audience won’t realise that they’re your target audience, and won’t find your business intriguing.

If you don’t have Product-Solution Fit, the customers who try your products/services will still be unsatisfied.

If you don’t have Product-Market Fit, your customers will overlook you and shop elsewhere, or won’t recommend you to other people like them.

Most importantly, these tests feel fair.

You don’t need to cheat - the only person you’d be deluding is yourself.

It is massively in your interest to fit all three types of fit, giving you confidence that there is a deep pool of motivated customers, who you know will love what you’re selling.

Customer-Problem Fit In More Detail

You probably have a good idea of what we mean by customer, but just to clarify; a customer is the person who pays you and who makes an active purchase decision.

They get a vote, and they are giving up something valuable (usually cash).

A lot of businesses have up to three different stakeholders in a transaction:

· The customer, who is paying you

· The end user, who ends up participating, or consuming the product/service

· The beneficiary, who is better off because of your products/services and the resulting changed behaviour.

Sometimes these are all the same person, like when you choose your own lunch at a shopping centre, you’re the customer, end user and beneficiary.

Sometimes these are two different people, like the boss choosing where to hold the staff Christmas party (one customer making a purchase decision, but 25 end users participating in the event).

Sometimes these are three different people, like the boss choosing to buy ethical and reusable Christmas gifts for the team (one customer making a purchase decision, 25 end users receiving Keep Cups, future generations or sea life benefitting from a very, very minor reduction in pollution and landfill).

We want to understand each of them, but with particular attention to the customer, who is the make-or-break factor in any purchase.

We want to learn how decisions get made, who pays, and how they measure value (even if they aren’t directly participating).

Jobs To Be Done

Once we understand who the customer is, we can begin to understand what they care about – and the number one risk to a new idea is that it solves an irrelevant customer problem.

Customers cannot care about everything, it would be too overwhelming.

We naturally prioritise and focus on the issues and opportunities that seem like real difference makers, and each of these has a trigger or moment where they rise to the surface.

These are called “Jobs To Be Done” – it’s similar to “Problem” but not as negative.

Some Jobs To Be Done are based on avoiding pain, some are mundane and some are fun and exciting.

e.g. “needing to get your car serviced” vs “choosing where to go on holiday”.

Each Job To Be Done starts with a trigger – a moment where the need or want suddenly becomes clear to the customer.

· You notice that one of your tires is deflated, so you’re going to quickly decide where and how to buy a new one.

· You’re watching a movie and suddenly get the inspiration to buy a new item of clothing that will likely look good on you.

· You hear a story about a company who used automation to free up 15 hours a week of time, so you start searching for apps and services that might work for you.

· Someone reminds you that Mother’s Day/Father’s Day/Valentine’s Day is only a week away, and you realise you have nothing planned so far.

They’re not all profound and they’re not all life-changing, but these moments are when new potential customers become available.

We want to have a decent understanding of when, where and why they happen.

Then there’s the customer’s limited budget, in terms of money, time and attention.

They can’t say “yes” to everything, so they will try to concentrate on the parts of their life and work with the highest “return on investment”.

We want to understand when, where and why these Jobs To Be Done become important, because that helps us meet customers where they are.

What are they typing into Google?

What is most important to them – quality, speed or price?

Do they want options or recommendations?

Do they have an amount in mind to spend?

What did they previously use to solve this Job To Be Done, and why might that old option be inadequate today?

High Value Jobs

Strategyzer have a great term for these priorities: High Value Jobs.

High Value Jobs have four tell-tale traits:

They are Important to the customer, and require some sort of outcome or resolution.

“Doing Nothing” isn’t a viable alternative.They are Tangible to the customer, in that the customer can clearly name that they are looking for a resolution, rather than a vague frustration or curiosity.

Sometimes customers need to start shopping before they can properly name the real job they’re trying to address.They are Unsatisfied, and no other product or service is adequately doing the job today.

hey’ll care about this job tomorrow if it’s not resolved today.They are Lucrative, and the customer is willing to pay a decent amount of money to get the right solution or outcome.

Lucrative doesn’t mean luxurious, it means that customers can pay at least a fair amount, and aren’t assuming that this will be given to them for free.

High Value Jobs are what make a customer base easy to work with.

These customers are motivated, hungry, ready to make a purchase decision, and are unlikely to waste your time.

If they miss one of the four criteria, they are likely to bail midway through the sales process, wasting their time and yours.

Some social entrepreneurs want to serve different parts of the market – people with low incomes or who don’t normally buy these sorts of things.

While this is a nice sentiment and they are likely nice people, you’ll want to ask yourself; is this objectively a good market to serve?

Or maybe; is this is good market to serve first?

Perhaps the people you like are the end user or beneficiaries of your work, not the customers making a purchase decision?

Product-Solution Fit In More Detail

There is a temptation to jump straight to “do we know how to manufacture this product/service at scale?”.

While that feels like a smart question, it comes at the wrong time.

If you know how to efficiently manufacture products that don’t help your customers, you will efficiently set fire to your money.

The details of the product/service matter once we know that these are giving customers what they truly want.

And in a lot of cases, founders are surprised by which parts of their products/services customer truly appreciate.

We had one client in the South Pacific that ran a coffee company, who was stunned to learn why his distributors and customers chose their brand.

The founder had guessed that it was to do with quality, flavour profile or maybe the story of it being so local.

Nope, none of those came up with customers.

When interviewed, the cafes, restaurants and hotels said “we stay loyal because your team clean our coffee machine when they’re here, and our staff don’t know how to do it”.

This moment of shock, a mix of devastation and feeling slightly complimented, is known to us as the “cleaning the coffee machine moment”, the realisation that customers have very different perceptions and priorities, but still come back for more.

You’ve probably got one of these moments coming your way.

If you do, you’ll want that moment to happen as soon as possible.

Behind every decision are two reasons – the good one and the real one.

We want to understand the good reasons that customers tell themselves and their friends, as well as the real reasons that drive their behaviour.

· Is it that your product saves them money in the short term or long term?

· Is it that you’re the most convenient to deal with?

· Is it that you have the best story?

· Is it that yours is the most durable, reliable or most trustworthy option?

· Is it that your venue, branding and team make people feel special?

· Is it that you are the most progressive or technically advanced?

· Is it that you’re the easiest option to explain to their staff or family?

Compared To What?

Most of these require a bit more context: “Compared to what?”

What’s the alternative?

What’s plan B?

If your company ceased to exist, what would customers switch to?

Sometimes this is compared to your nearest rival, sometimes this is compared to an alternative solution, or even the option of doing nothing.

We can call these “Direct and Indirect Substitutes”.

Direct substitutes are nearly identical products and services to yours, like when a customer chooses between brands of running shoes.

Indirect substitutes are drastically different products and services that address the same underlying goal, like choosing between flowers, chocolates, tickets, jewellery or buying nothing for Valentine’s Day.

We want to understand how our customers consider their options:

· Where are they?

· What are they choosing between?

· How much time do they have?

· What do they use to measure value?

· How much is their budget?

This helps us determine what our products and services will be compared to, and what information and selling points we will need to highlight to the customer.

As Seth Godin said, the two main strategies will be either to be better than the competition, or cheaper than the competition.

Either one can work, but trying to be both at once is a recipe for disaster.

If it’s better, better than what and how will the customer know?

If it’s cheaper, cheaper than what and how will the customer measure the savings?

The Active Ingredient

Most medicines have two types of ingredients, the active ingredient that makes the change, and the inactive ingredient that protects the active ingredient, so that it is absorbed at the right time.

e.g. Panadol’s active ingredient is paracetamol, whereas the other powder or the coloured pill casing is an inactive ingredient that assists with absorption.

We want to identify which elements of our work are the active ingredients, that serve or delight customers and live up to our promises.

Perhaps it’s your team, your brand, your story, the quality of your materials, your track record, your cost efficiency or buying power, etc.

What enables you to produce a better or cheaper result than your competitors?

Is there any sort of “moat” or barrier to your competitors doing exactly the same thing?

Is there another way of delivering/absorbing this active ingredient – how else might we get it to our customer?

Are there more/less pleasant ways, or faster ways, or cheaper ways?

Finally, how strong is your solution?

Speaking of Panadol, there are three “strengths” of customer benefit:

· Vitamins – nice to have, some benefits that emerge over time

· Painkillers – important to have, clear benefits in the short term

· Oxygen – essential to have, instant benefits for the user

Startups are commonly advised to search for oxygen-level benefits, as these customers are more motivated and will get good use from your products and services.

In reality, this is hard to get right from Day 1, so a painkiller might be a realistic starting point.

Your job is to listen to your customers – how urgent is the problem and how motivated are they to find a good solution?

Product-Market Fit In More Detail

Product-Market Fit is a fancy way of saying “We have a match between a pool of good customers, and a product/service that they genuinely love”.

More bluntly, you have lots of customers saying “Shut up and take my money”.

They’re not being polite, they’re not trying to give you compliments, they want what you’re selling for their own reasons, and will recommend others to do the same.

When you reach that point, the business has great potential, and until you reach that point, the work will remain difficult.

We should have evidence of enthusiasm from the market.

This might look like a pre-sales campaign, a successful crowdfunding initiative, early registrations and sign-ups, or multiple conversations with the same customers as they get ready to make a purchase.

The two signs are what Rob Fitzpatrick describes as “Commitment and Advancement”, where customers either give up something of value to progress the deal, or keep taking the next step in the journey.

e.g. putting down a deposit, agreeing to a trial period, introducing you to their boss, arranging the next meeting to discuss their options.

These are not just kind words; they are tangible actions and they indicate real interest.

We want to take courtesy and cultural politeness out of the equation; subtracting their nice words and focusing purely on their actions.

We know that not every conversation will result in a sale, but the absence of commitment and advancement is a huge red flag.

If you’re not sure if there’s genuine appreciation in your market, ask youself “If we were to disappear tomorrow, who would miss us?”.

Would your trial users complain and ask you to keep going?

Would customers notice your absence?

Where would they go next, and what would they buy instead?

These are all sincere forms of validation – signs that customers know who you are, like what you do, and trust that you’ll deliver what you promise.

This stage involves a lot of work, but it shouldn’t be too hard to find and impress your next batch of customers.

Investors love these signals, they demonstrate that you’re ready for growth.

Robert Herjavec, one of the sharks on Shark Tank, says “You want to invest after the sales come in; you want to invest to support the sales, not ahead of the sales”.

e.g. imagine two businesses – one has a line of customers out the door, struggling to keep up with demand and in need of new equipment and premises.

The other has hardly any customers, and wants money for product development and marketing.

Who is easier for an investor to say “Yes” to?

Investment is good at magnifying a situation, not changing a situation.

When it’s working at a small scale, investment can make it work at a bigger scale.

When it’s not working at a small scale, investment is unlikely to turn a bad offer into a popular one.

Creative Thinking For Business Ideas

Some people find it frustrating that there is no pre-set formula for finding business ideas, wanting a paint-by-numbers approach that can somehow guarantee them commercial success.

Entrepreneurship can be confusing and fatiguing, but finding ideas shouldn’t be agonising.

There are several good reasons why you’ll need a creative approach rather than a formula:

· Customers change all the time, and often seem “irrational”

· Markets change all the time, often in long cycles

· Technology changes all the time, often unpredictably

· Competitors are always moving, starting and closing without warning

· Lots of people have very similar ideas, and only one succeeds because they happened to show. up at the best possible time

· Talented team members come and go

· Well intended ideas create unexpected problems

· Sometimes two problems can end up solving each other

That means that an idea you dismissed 18 months ago might be far more relevant today, and vice versa.

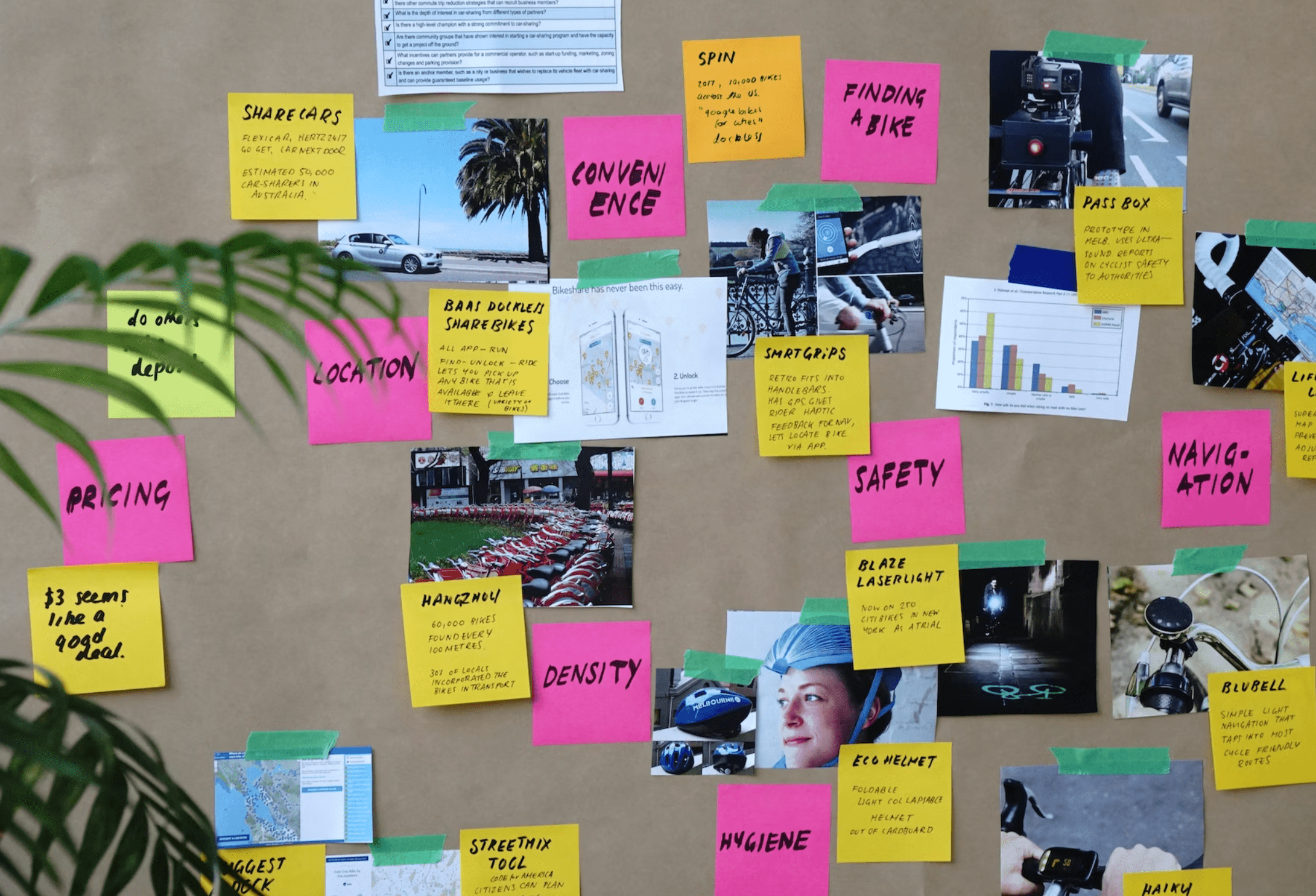

Entrepreneurs get to explore lots of options, dream up lots of ideas, smash them together or strip them back to their bare essentials, looking for signs of a promising startup.

Most ideas will not be quite right, but you don’t need them all to work.

The goal is to generate lots of ideas, to let them breathe and take shape, then assess them and choose what to develop.

And contrary to what you might think, there isn’t a “Good Ideas Tap” and a “Bad Ideas Tap”, there’s just one “Ideas Tap”.

Our job is to get the ideas out, then let the strong ones rise to the top.

That might mean that your next job is to let the tap run for a while, filtering the ideas at a later point.

Some Creative Prompts

Here are some helpful questions and nudges to start your off:

· If my customers had a magic lamp with a genie, how exactly would they phrase their three wishes?

· If I could help a customer 1-1 and money was no object, what would I do for them?

· If we could teach a group of customers some new skills, what skills would they be?

· If I could create great recordings for my customers, what would they cover and what format would they prefer?

· If we had to assemble a good-enough solution out of competitor’s products and services, what bundles would do the job for our customers?

· Imagine you see an ad for a rival business, and your stomach drops. They’ve launched an amazing offer with a compelling tagline and the perfect imagery. You’re immediately sure that every customer is going to pick this over all the other competition. What did you picture? Can you build this idea first?

· If we drew up a hypothetical menu of offers and options for our customers, what would we list and how much would we charge? Which ones do we think customers would choose? Could a few options be 5x more expensive than the others and still be great value?

· How would Steve Jobs have approached this? Michelle Obama? Richard Branson? What entrepreneurs do I admire and how would they view this situation?

· Are we trying to “have our cake and eat it too”? Would customers prefer several different options, each more specialised or flexible?

· What if we had to give the core product/offer away for free? How would that change our approach, and what could we offer as a follow-up or extra?

· What if we swapped the traditional products in this industry into services? Or swapped the traditional services into products? What would that look like?

Apprenticing With The Problem

Jessamyn Shams-Lau spoke about the idea of “Apprenticing with the problem” before rushing to a solution.

The temptation is to jump to answers, without fully understanding why things are the way they are and why the problems still exist (much like our Problem Trees).

Apprenticeship is a good analogy for what’s involved, the apprentice gets to participate in the work, learning as they go, often in unglamourous circumstances.

This apprenticeship gives you a hands-on understanding of the industry and your customers, and is likely to both frustrate and inspire you.

Both are great sources of ideas.

It’s also the bare minimum for creating solutions for other people.

As a general rule, don’t try to create solutions for people you don’t know or problems you don’t understand.

Good founders are naturally curious about people and problems – a lack of curiosity might be a sign that this isn’t the right field for you right now.

In practice, an apprenticeship doesn’t need to be a formal arrangement, it might be a volunteer role, a job in your field, trying to create something yourself, joining a board, or spending quality time with the people who are experiencing a particular issue.

In some circumstances, you might be able to get paid to prototype – providing you with an income while you try out new ideas and learn from what already exists.

There are no set timeframes, but be wary of anything that lasts less than three months, that’s usually not enough time to understand seasonality and complexity.

Scratching Your Own Itch

Yee Tong from School of Thought once said “Every time you hear yourself bitching about something, you identify a market need”.

Your complaints might not be unique, but they are evidence of an unmet problem, and usually one that affects a lot more people than just you.

This has often sparked inventors and new founders to find ways of addressing their own concerns, either by piecing together solutions, crafting their own prototypes, or lobbying for change at a higher level.

You might find this as a good creative starting point:

· What do you hear yourself complaining about?

· What do you hear yourself evangelising about?

· What do the people around you complain about?

· Where do you hear people say “I can’t believe we still…”?

· What problems have you resolved in your life and work?

· Where have you put together a barely-good-enough solution?

· If you had a magic lamp with three specific wishes for your lifestyle, work or hobbies, what would you wish for?

· What do the above have in common? Are there recurring themes?

So to recap:

1. A good business opportunity has three types of “fit” (Customer-Problem, Product-Solution, Product-Market).

2. Customer-Problem fit requires us to understand our customers and their Jobs To Be Done.

3. Product-Solution fit requires us to understand our competitors and substitutes, as well as which elements are our “active ingredient”.

4. Product-Market fit requires us to run tests and experiments, looking for signs of “commitment and advancement” from our customers.

5. Entrepreneurs need to be curious and creative in order to spot problems, complaints, trends and gaps that all point to a good business opportunity.

6. You can use weird prompts and questions to spur your thinking, then let the "ideas tap” run for a while, sorting the good from the bad at a later date.

7. Impatience, disinterest and arrogance kill your ability to spot ideas and test them properly.

8. You might need to apprentice with the problem to understand it (and yourself) in more detail.

Generating and evaluating ideas is notoriously unpredictable, but it’s still a great process that is well worth your time.

If we understand the three types of fit, we can then explore lots and lots of ideas without fear and without falling in love.

We can hear our ideas out, giving them the chance to show their potential, and feel confident that our three tests will be honest and fair.

Most importantly, the process of creating ideas, apprenticing with the problem and talking to customers should be entertaining for you.

It might not be immediately profitable, but it should be satisfying, or else it might indicate you’re in the wrong field or are here at the wrong time.

And remember, when you hear yourself bitching, you identify a market need…