Finding And Naming Your Cause

“Working hard for something we do not care about is called stress, working hard for something we love is called passion.”

- Simon Sinek

Every entrepreneur is faced with two variations of the same question:

When times are good, people ask “Why did you start this business?”

When times are tough, they ask themselves “Why did I start this business?”

In both cases, it’s easy to give a quick, dismissive answer.

But the deeper, more complex answer is important, since it’s going to help you design your business, navigate new possibilities, and give you fuel when the work gets hard.

In this article, we’re going to explore how a founder or brand identifies and names their cause, and how to use these stories to your advantage.

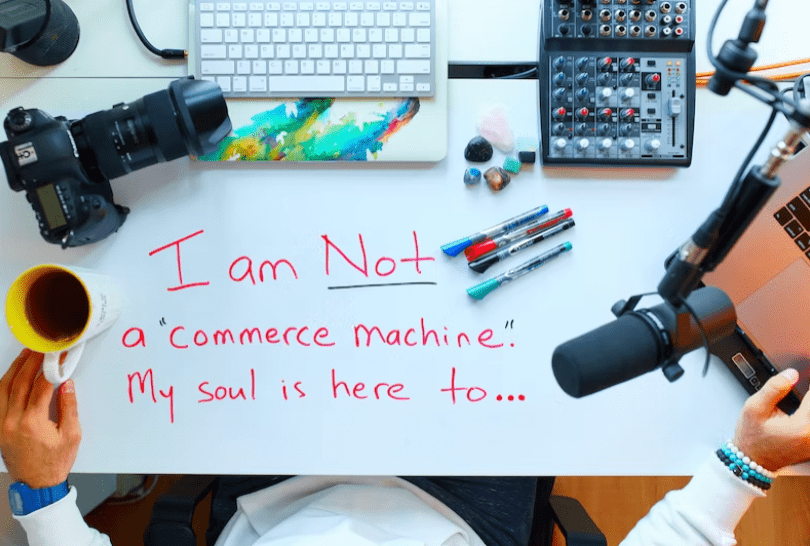

What Do You Care About?

Causes can be tricky to describe, because they’re as much about emotion as they are about logic.

Logic can point out a gap in the market, where there’s potential to make money.

Causes aren’t lucrative; most of them will cost you money at first, but they inspire you to make or do things that can become lucrative further down the track.

In fact, that’s a good test question:

Test Question 1 – What am I happy to do for free? Where do I naturally spend my money?

A cause usually simmers away in the back of your mind.

You might watch videos about it on YouTube, go to community events in your area, or make lists of ideas in the notes app on your phone.

It’s something you research, practice, debate, or talk about with your friends and family, even if they have minimal interest in that field.

Test Question 2 – What are my friends sick of me talking about?

Sometimes causes come from a place of hope and optimism, a desire to see improvement or something remarkable.

“I want to build a theme park based on the life and work of local historical figures”

More often than not, they come from a place of anger and frustration.

e.g. “why is it still so hard for someone in a wheelchair to visit our city?”

“how come so many young people know how to manage their money?”

“there is shockingly little support available to Indigenous artists”

Anger is a good source of fuel, one that’s more dependable that hope or optimism.

That fuel is important, since you’re going to make progress in your work on days when you don’t feel like it, and that dissatisfaction can help propel you out of bed each morning.

Test Question 3 – What makes me angry? I can’t believe it’s 2023 and we still ______”

A cause is usually connected to an underlying desire or an entrenched system – not things that can be solved in a weekend.

You’ll spot surface-level symptoms of deeper issues, and while those symptoms should be addressed, they aren’t the true problem.

For example, people lobbied restaurants like McDonalds to stop using plastic straws, and they eventually changed to paper.

But you wouldn’t imagine that those campaigners are now “done” or “content” with McDonalds’ actions, there’s so much more progress to be made, be it in the fields of animal cruelty, food miles, plastic waste throughout the value chain, children’s nutrition, adult nutrition, living wages, etc.

The straws are just a tiny scratch on the surface of the problem.

It's good to ask: is the problem due to the law, or due to a long-held cultural belief?

Do we need a new technology, a new way of thinking, or a new voice in the market?

It’s helpful to think about which part of the issue you care about – if you go to small, it’ll feel tokenistic, and if it’s too difficult or too vague it’s unlikely to build traction.

Test Question 4 – How deep is the problem? What are surface level symptoms and what are the deeper root causes?

A cause might be in a “likeable” field, but where most people aren’t taking enough action or moving fast enough.

There might be nominal agreement that “something should be done”, but leaders or consumers are hesitant to genuinely change their behaviour.

e.g. people want to address climate change, but are resistant to reducing the amount of meat they eat each week.

Or an institution might claim to support diverse team members in advancing their careers, but have no funding or initiatives to make that a reality.

These are jarring when you see them – it highlights that you believe something they don’t, and that’s a big clue that there’s something connected to your cause.

It might be that not enough is being done, or that the wrong people are at the table, or that certain behaviours should be made more convenient, or that bad behaviours should be made less convenient.

Test Question 5 – What do I believe that others don’t?

These questions are a way of poking and prodding yourself, to see where there’s a strong feeling.

These might look something like:

“We need good quality, affordable plastic replacement options for hospitality businesses. Business owners want to do the right thing, but not if it’s really difficult or prohibitively expensive. We want brands to switch to sustainable materials, without compromising on usability or aesthetics”

“We want to see Indigenous culture and designs represented in all parts of fashion – something people wear with pride every day. That means supporting designers, developing supply chains, strong marketing, a real celebration of our people and our art”

“Young people are the future of this country, and they are so uninspired by our political system. They are ignored and dismissed by a broken, unfair system. We want to encourage the next generations to take an active interest in politics, support them in their careers, and help their views be heard in the halls of power”

“Too many women stay stuck in abusive situations because of the lack of basic supports available to them. It should not be this hard to find employment, housing and access to proper support services”

You might notice that all of these describe a problem, but not a solution or a business model.

They describe an end result, new behaviours or new power dynamics, but aren’t proclaiming to know exactly how we’ll get there.

What Else Exists?

Here’s some mixed news for you: you’re rarely alone in the world of social business.

The nice part is that you’ll have a community of practice – other people and institutions who have already been talking about your field, trying new initiatives, making progress and telling stories.

The tricky part is that you probably won’t love everything they’re doing, be it that they’ve gone in what you think is the wrong direction, or aren’t going far enough.

So while it’s good that you’re determined to do things differently, it’s also important to not barrel in with youthful arrogance, telling everyone that they’ve screwed up and that you know better.

Even if you’re right, it’s still not a wise thing to declare to your prospective partners.

The first mistake new people make is to announce an idea that already exists – this can be embarrassing since it shows that you haven’t done your homework.

Your job is to research your field, to see what is out there, what’s been attempted, where are people talking about going next, and which actors have different priorities.

There’s room for a lot of organisations, in fact it’s impossible for any one of them to be all things to all people.

The second mistake is to announce duplication without explanation.

You are of course welcome to do the same things as other groups, but you’ll want to have an explanation of how this is different.

You might focus on:

· Affordability (ours is more accessible to people with a budget of…)

· Inclusion (ours is more accessible to people like…)

· Specialisation (ours is focused purely on…)

· Location (ours is focused on the area of…)

· Materials (ours are made from…)

· Longevity (ours are designed to last for…)

· Partnerships (ours are compatible with… or will be rolled out through…)

There are two reasons for this; firstly it’s courteous and avoids stepping on toes (until you mean to step on toes), and secondly, the incumbent’s approach is probably not going spectacularly well, or else you wouldn’t need to duplicate it.

The third mistake is missing out on sensible partnerships, which can save you a lot of time and energy. If there are other groups with the similar/aligned causes to yours, they might be able to connect you to suppliers, assist with insurance, share office space, recommend you for speaking opportunities, help manufacture products or deliver services, etc.

I once heard someone say “we have 37 charities focused on children’s cancer”.

That sounded good to me, until they continued; “that means we have 37 CEOs, 37 offices, 37 Christmas parties, 37 bookkeepers…”.

That’s a lot of administration costs and overheads, let alone how overwhelming it is for donors.

You’d probably assume that there could be a lot of effective mergers, maybe down to 6-10, leaving more funds available and forming stronger projects to actually do the core work in preventing/treating cancer.

You might discover that you don’t truly want to start a new business, but actually want to run a project in partnership with an existing organisation.

Or maybe you want to assemble people from other groups around a common goal or project, rather than employing an entire team.

Or maybe it needs to be new and different, maybe different is what will help you achieve different results.

The important thing is that you’ve explored what’s out there and considered your options.

Telling Your Story

If you’re going down a particular path, it can be hard to remember that 99.99% of the world won’t know anywhere near as much about this subject as you do, so most storytelling will need to begin with some quick education.

This is called “the curse of knowledge” – you forget what it’s like to not know all the things you’ve learned, and will have to deliberately set the scene.

This usually involves some sort of surprise or shock for the audience, who probably thinks that they understand the problem today.

Once they understand the issue, then you can talk about your cause, and what you intend to do about it.

A rough template might look like:

“You know how_________”

“In fact, ________”

“But _______”

“That’s why we’re dedicated to _________”

“And will _______”

So for community housing, this might sound like:

“You probably don’t know anyone who intends to become homeless.

But studies show that each of us are two bad decisions away from being homeless ourselves.

And you’d be horrified at the state of most rooming houses today.

That’s why we’re dedicated to creating inclusive community housing, places where people who are otherwise sleeping rough can have a safe, secure and welcoming home.”

That’s a basic example, but it works – we’ve tried to reframe how people see homelessness, going from something that happens to other people, to something that could happen to you.

This brings a new appreciation for a genuinely welcoming house, and why they should care about how vulnerable people are cared for in society.

It’s a good rule; your audience doesn’t need to instantly agree with your cause, but they should be able to relay it to someone once they’ve heard it.

If it’s bland (“to help people reach their full potential”), people will forget it or misinterpret it.

You want your story to create a clear mental image, and invite a question or participation from your audience.

As a side note, it’s good to remember that your story is bound to be unpopular with some people, since as we explored with Test Question 5, you believe some things that they don’t.

These differences of perspective might come from ignorance, cultural views, jealously or rivalry, and the fact that some people are awful.

If you’d like to see this for yourself, all you need to do is find things you like online and look at the comments section.

Comments sections remind us that disagreement is inevitable, and that some people nitpick for the sake of it.

For this reason, your story will not and should not receive universal approval, or else it becomes too bland and forgettable.

Your Cause Is A Compass

A cause is not the same as a business model, but it should guide and influence your business model.

It might influence the products you sell and how they are made, so that you don’t get exposed as hypocrites.

It might influence who you hire and how you work as a team, so that you can create opportunities for the people you want to support.

It might influence your pricing strategy, so that you’re happy with your position in the market and who can afford to shop with you.

It might influence what you do with your surplus cash, which can be reinvested for growth or set aside for important causes.

It might influence when and how you choose to grow, both in terms of where you are based and in who has ownership/control of the company.

Businesses have a lot of choices available to them, and some of those choices clash with your values. An entrepreneur can try to “make money at all costs”, but if those decisions exploit the people you claim to serve, or destroy the environment you claim to protect, you’ll likely face a backlash.

You don’t have to be an ethical perfectionist, but nobody likes a hypocrite.

Your cause can also offer guidance when you feel lost or drained, offering a reminder of why you started this work and why it should continue.

Rather than setting arbitrary financial goals, you can measure your success in how much progress or positive change you can bring about.

Like a lot of things in life, this fades over time, so it’s important to frequently remind yourself and your team about why this work matters, who it helps, and what progress has been made so far.

Some people like to collect photos, screenshots and notes they’ve received and keep them in a jar at their desks, acting as a little pot of inspiration for the days where they feel like everything is hopeless.

It certainly can’t hurt.

You Might Have Several, And They Might Share Themes

You’re allowed to have several causes, and don’t have to narrow them down to one single statement.

They might include strong feelings on:

· Local or federal politics

· Marriage equality

· Climate change

· Affordable housing

· Nutrition

· Supporting the arts

· Cryptocurrency

· Access to education

· Mental health support

· Domestic abuse

· Religious freedom

· Financial literacy

· Safety at night

· A living wage

· Access to healthcare

It’s worth examining them as a set, to see if there are recurring themes amongst seemingly diverse fields.

A common theme might be that they all promote independence, or that they benefit from standardisation, or that they are anti-bullying, or that they enforce environmental responsibility, or that people would benefit from embracing technology, or that people should have more choices, or that people should have fewer choices.

These are big clues to what you value and how you see the world, which is helpful to articulate before you try to tell your story.

There are likely other people whose worldview is the total opposite, and while you don’t need to agree with them, it’s helpful to remember that they are operating from a different set of values.

For example, if you believe “People deserve better” and they believe “People are where they deserve to be”, you’re unlikely to see eye to eye.

Similarly, you might believe “Local groups should co-design the systems that surround them” and others believe “people should use the best possible systems”, then you’re probably going to have an issue over the word “best”: does it mean the best fit, or the most critically acclaimed?

This is why startups often struggle to partner with institutions – the startup wants change and experimentation; the institution wants things to stay the same and to be predictable.

Neither of you might be bad people, but you’d probably be bad partners.

Causes Aren’t About Perfectionism

One of the differences between a cause and a vision is that a cause is an ongoing campaign, whereas a vision describes a beautiful distant future.

While a compelling vision can be motivating, we don’t want that to become our benchmark of success.

You want a description of a cause that is meaningful and can be worked on in bite-sized increments; the difference between “solving global hunger” and “nobody going hungry in my neighbourhood tonight”.

Perfectionism has a sweet voice but it keeps you small and discouraged – we want to be able to celebrate early drafts, prototypes and milestones along the way.

If your perfectionist vision causes you to criticise all of the early progress, you’re likely to burn yourself and your team in service of your ego.

Putting It Into Words

Kevin Starr from Mulago Foundation recommends a technique called The Eight Word Mission Statement.

This is comprised of a verb, a target group and a measurable outcome, such as:

· Save kids’ lives in Uganda.

· Rehabilitate coral reefs in the Western Pacific.

· Prevent maternal-child transmission of HIV in Africa.

· Get Zambian farmers out of poverty.

What’s great about this technique is that it strips away all of the flowery, ornate language that gets in the way of clear communication.

By focusing on who it’s for, what you want to do and how you’ll know it’s working, you have a blunt and inspiring summary of what you want to achieve.

Try it for yourself, or try a few versions – which ones sound right to you?

What’s Next?

Once you can name your cause, tools like The Problem Tree and a Theory of Change and great for explicitly defining what needs to change and how you can change it.

We’ll explore both of these in upcoming posts.

If you don’t yet know your cause, your job is to become a good observer of yourself – listening for things that excite and upset you, or conversations where you have strong opinions, or people/beliefs that annoy you.

What do these feelings have in common?

What do you believe that other people don’t?