Spotting And Validating Assumptions

Our brains are very good at taking shortcuts, which are normally helpful in our daily lives.

If we’ve seen or experienced something before, we figure that’s just what always happens.

If we’ve been tricked or burned, we naturally avoid those things.

We form assumptions and stereotypes (but we would never want to admit it in public) about what different types of people or industry might be like, what things are good and what things are a scam, and what we might enjoy in the future.

The trouble is, a lot of these assumptions are wrong – they’re either obsolete, overly simple, too harsh, too naïve or don’t match the specific scenario that we’re in.

Something that was “obvious” in the past might no longer be true, and ideas that were previously “impossible” might be within our reach.

So when we start to think about business ideas, we naturally populate our vision and plans for the future with assumptions, and some of those assumptions are wrong.

What’s even more insidious is that the faulty assumptions will likely sound true, which is why they’ve previously gone unquestioned.

Time to go and dig them up.

Here are some common examples:

“People will switch to…”

“Customers will find us through…”

“Legally I’m sure it’s fine to…”

“We’ll just hire someone to…”

“That should be done in, what, two months?”

“We probably can’t go much bigger than that”

“If we only had…, then the problem of… would be a thing of the past”

Faulty Assumptions Are Expensive

You’ve probably started to make assumptions about price, value, hiring, or how many customers you can serve in a day; things that are somewhat within your control.

Then there are broader assumptions about the market, your competitors, the economy, technology, your suppliers and your co-founders.

You can’t control these, so you’ll have to pay close attention to them.

The most dangerous assumptions are the ones that feel so obvious or given that we assume they can’t or won’t change.

You’ll verify something to be true today, but it might be radically different in 3-5 years.

Not only do things change drastically, but we find it hard to forecast which types of things will be drastically different in the coming years.

That makes complacency a business-killer.

You can see assumptions in almost every big shift or failure in the business world:

Kodak assumed that people were deeply committed to using film cameras.

Movie studios assumed that Avatar was the start of the 3D future.

Taxis assumed customers had no alternatives to choose from.

WeWork assumed that every city was like New York and San Francisco.

Nokia assumed that they had loyal customers and didn’t need to compete with Apple and Android.

Those are famous examples, but these play out in businesses all the time:

Social entrepreneurs assume customers will do the environmentally responsible thing even if it’s inconvenient.

Founders assume that their linchpin team member will never leave.

Owners assume that their competitors will do exactly the same things that they’ve always done.

New entrepreneurs assume that if an idea was good, someone would already be doing it.

Freelancers assume that they can hire someone who will do as good of a job as them.

Managers assume that people are rational and will make sensible, predictable choices.

Investors assume that security comes from holding steady and retaining your advantage.

They all sound so credible that questioning them feels inconvenient, or even ridiculous.

And that’s why we need to proactively check them.

Evidence vs Guesses

The fundamental difference between an assumption and a fact is evidence, and not all evidence is equally valuable.

Evidence should be credible, relevant, measurable and clear.

Credible: who gathered the evidence, do they have a notable bias, do they have a sophisticated understanding of this field?

e.g. Stanford Social Innovation Review is more credible that someone anonymous on Twitter

Relevance: is it recent, is it localised, were there other contributing factors?

e.g. a small journal’s statistics and commentary on homelessness in your area is more relevant than a comprehensive study conducted in a different country in 2006.

Measurable: is it quantifiable, do we have something to compare it to, can we keep track of how fast things change?

e.g. Clickbait titles like “People are going crazy for…” are less helpful than “Annual customer spending per person has gone from $116 to $175 in the last five years”

Clear: are there too many variables, is the language explainable at a barbeque or pub, would my peers read this data and describe it the same way?

e.g. A country’s GDP is credible, relevant and measurable, but doesn’t tell a clear story, whereas an A/B test of your ads shows you exactly which option performed better.

Realistically, you will likely have to make the most of what information is available to you.

For broad topics like the PESTEL categories they talk about at business school, you might need to find secondary research that summarises sophisticated studies.

For specific topics like customer preferences, production capacities and your Unit Economics, you probably need to do the research yourself; since the circumstances are so unique and you gain so much from the process.

Where Does Confidence Come From?

A lot of entrepreneurs resist the idea of validation because it feels like a waste of time – they know what to do so why second guess it?

A helpful way of thinking about it is to try and prove something to yourself, running the experiment because it will make you smarter and more confident, rather than doing it for the sake of an argument with your investors.

Sometimes there’s an element of fear – founders don’t want to go hunting for that evidence if that evidence tells them not to proceed.

One of our clients famously said “I don’t want to test it, because the tests might make me not want to do it” – there was a long pause and a big laugh as we all processed what they meant.

There are a few mindsets shifts that have proven to be helpful:

Things are rarely as good or as bad as you’d think.

The hype of a good idea and the depression of a setback are both exaggerated in your head, the truth of the situation is usually somewhere in between.

As Marie Forleo said, “Everything is Figureoutable”.

Very few problems are impossible or laws of the universe, and can be addressed if you have a good team and a level head.Entrepreneurs should learn how to “cap downside risk”.

This is where you deliberately lower the cost of a mistake or problem, like running a low-commitment pilot, insuring yourself against catastrophe, creating a plan B, C and D ahead of time, finding a buyer for any unsold stock, etc.

This allows you to treat experiments like a scientist, not someone whose life savings are on the line.First-hand experience is not a waste of your time, it’s what gives you the right to design solutions.

Founders should want to get their hands dirty, to meet their customers, to know how the proverbial sausage is made.

Not only is this cost effective at first, it also helps them make better design decisions as they pivot and grow the business, and reduces the likelihood of large mistakes.Splitting out each of the variables shows you what matters.

If you run ads on two different platforms with two different messages at two different times of the year with two different budgets and two different offers, how will you know what did/didn’t work?

It’s so tempting to compare the results, but you won’t know why the better one was the better one – the timing, the channel or the message?

Running lots of tests takes longer but it means you actually understand where better performance comes from.Repeat business is the ultimate compliment.

Kind words are nice, but if they aren’t matched with a second purchase or a referral to others, then they might be covering up an unpleasant truth.

Wise founders know to watch how customers vote with their feet and with their wallets – that reveals what they really believe.Egos are expensive.

In a lot of cases, the only thing preventing people from checking their assumptions is that they worry it will make them look silly.

Aside from the fact that this is a bad reason, it’s not even logical: your ego will take a bigger hit from a bigger failure, so it’s in your ego’s interest to validate your assumptions early.

If you want to double check these, listen to founders talk about what they learned from previous businesses or past failures.

You’ll likely hear them talking about:

Traps that stemmed from flawed assumptions

Overreactions to good and bad news

Rushing in too quickly to a good idea

Finding success from tweaking different parts of the model

Insights from observing customers in the real world

The importance of getting the formula right before you try to scale

How To Get Started

The best place to start is to step back from your ideas and review them with fresh eyes.

This is often easier with a “critical friend”, someone who will nudge you to talk through why you believe what you believe and who has your best interests at heart.

Your job is to systematically work through your ideas and stories, trying to verbalise what you intuitively believe without sounding defensive.

Here are five helpful labels to assign to your assumptions:

“This is a fact or a law and will not change any time soon”

“This is pretty much a given and we’ve seen it ourselves”

“This is an educated guess based on past trends and research”

“This is borrowed from a smart friend or something we heard”

“This is a total guess because we had to start somewhere”

A good way of doing this is to colour-code your tools, canvases and documents with green, yellow and red dots.

Green dots indicate a validated assumption, yellow indicate that a test is in progress, and red dots are unvalidated.

That helps you keep track of which aspects of your work have been verified, showing all team members, investors or advisors as to what should or shouldn’t be questioned.

When you find an assumption that you’re not fully convinced about, it’s time to find more answers or design a test.

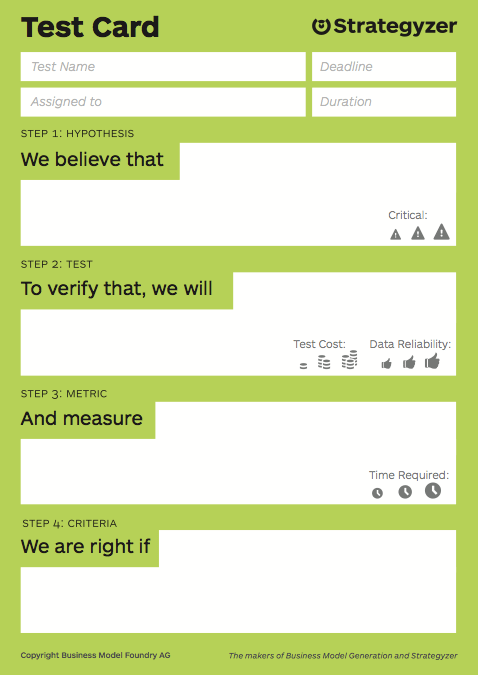

Tools like The Test Card are helpful because they nudge you with four prompts:

1. We believe that…

This prompts you to name your assumptions, including the ones that seem like a given.

We particularly want to list the assumptions that would be devastating if they were to be wrong.

2. To verify that, we will…

This prompts you to take an action, not just think about the assumption.

You don’t need to second-guess yourself, verifying is a double-check for your own curiosity and your own protection.

3. And measure…

We want some sort of metric that will help us prove or disprove the assumption.

“A vibe” is not conclusive nor is it evidence, but it might point you towards something objective and measurable.

4. We are right if…

We need to set the pass/fail criteria in advance, so as to not skew the outcomes of the test or try to rationalise unflattering results.

This prompts you to name your definition of success, which is helpful to think about.

If you are looking for inspiration, you’ll enjoy the book Testing Business Ideas by Strategyzer, which is like a cookbook of 44 different types of test for different stages of business ideas.

Out of the 44, there’s likely 4-5 options that are relevant for you, breaking them down into simple steps and suggesting some good metrics.

All assumptions deserve and require a double-check.

If they’re right, you’ll feel smart for accurately reading the room.

If they’re wrong, you’ll be so glad you found out now and not in a few months’ time.