How To Use A Business Model Canvas

The 15-Second Summary: The Business Model Canvas is a one-page business plan.

It describes how you win and delight customers, how your team works behind the scenes and how you consistently make money.

The canvas can help you design a strong model, and spot ways of improving your business.

The 60-Second Summary: The Business Model Canvas is one of the greatest modern design and strategy tools.

You’ve probably heard of it; it’s used in almost every growth program and accelerator for a good reason - because it consistently works.

It helps you describe what makes your company desirable to customers, feasible for your team to run, and viable enough that you consistently make money.

There are a lot of “explainer” articles online that give a quick overview of the tool, but the benefit comes from doing a deeper dive into every part of your idea.

By digging into each of the nine boxes and seeing how they fit together, you’ll find ways of improving your business and get your team on the same page.

This detailed guide will walk you through the process, with examples, questions and traps for each part of the canvas.

It doesn’t tell you what to do, it highlights your options so that you choose what to build next.

What Is A Business Model?

A motivated entrepreneur has an overwhelming number of choices to make:

· What industry should we be in?

· What type of company do we want to be?

· Who will be our customer?

· What will we sell them?

· How will we find and delight these customers?

· What will we outsource and what will we do ourselves?

· How do we make our money?

· What sort of “shopfront” will we have?

· What will help us succeed?

When an entrepreneur thinks about these questions, they are thinking about their business model – the story of how all parts of the business work together for success.

This is an important set of decisions; it is impossible to be all things to all people, and so the entrepreneur will be making a number of trade-offs.

They will likely take inspiration from a range of companies who have come before them, selecting a combination of elements that will allow them to consistently delight a customer, beat their competitors and make a surplus.

Business Model Design

If you don’t proactively think about your business model, you’ll feel lost, stuck, or will make decisions that you later regret.

You don’t have to write an enormous Business Plan either – the model should fit on a single page or whiteboard.

It’s a live document, one that constantly evolves and changes throughout the year.

And it should change; the market changes, your team changes, your competitors change, the broader economy and society changes – so if you want to stay relevant, you’ll need to be thinking a few steps ahead.

This is the field of Business Model Design – dreaming up new ways of running a business (or several businesses) that is sustainable, meaningful and profitable.

It’s not easy, but there are a lot of great resources and support programs that can make the journey clearer and a bit less daunting.

The work is never “done” – you’ll be doing this for as long as you’re running companies.

Fortunately, by learning some timeless principles and practicing with today’s best tools, you’ll build a transferrable set of skills that you’ll carry to every project.

Desirability, Feasibility and Viability

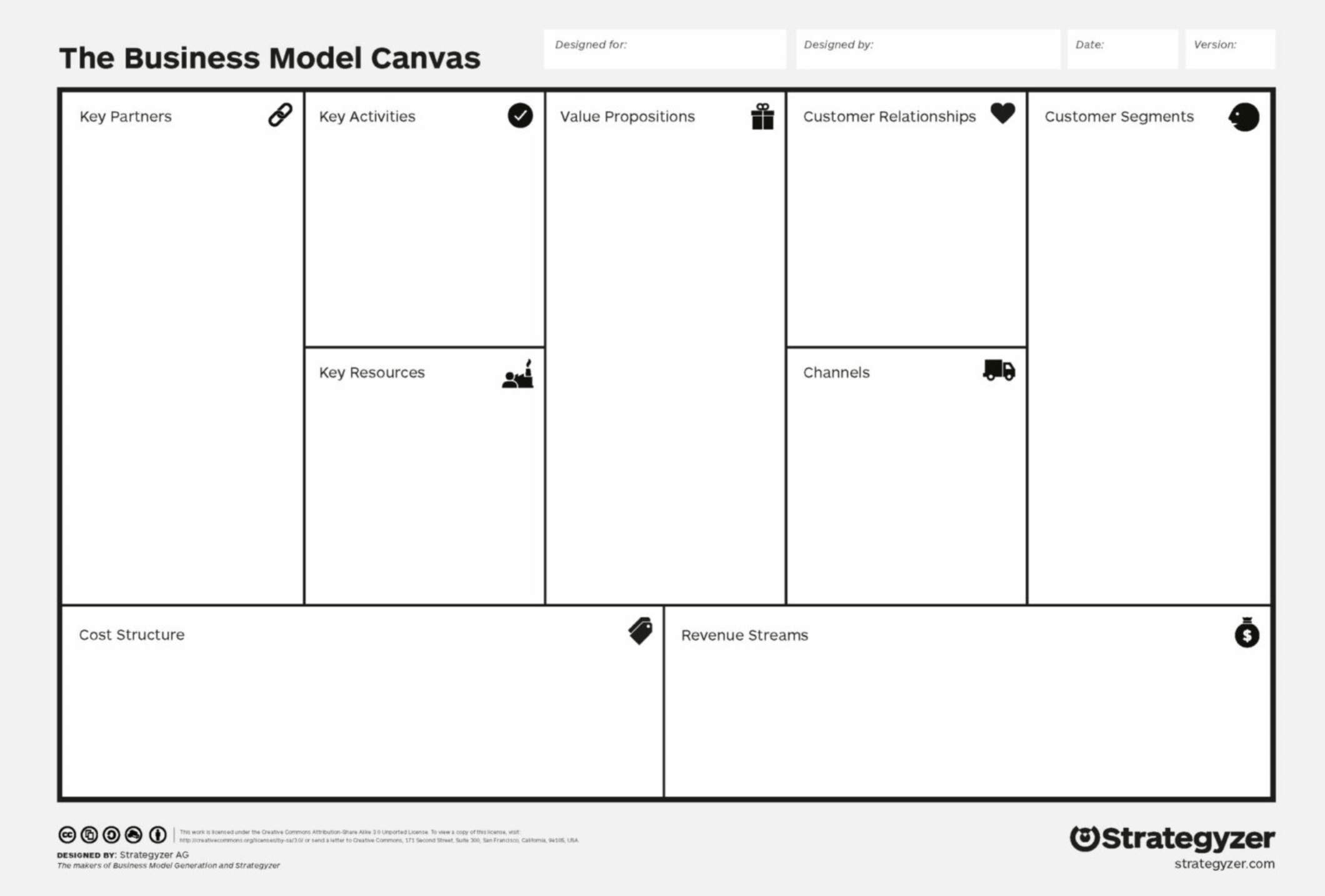

The Business Model Canvas is made up of nine boxes, but these boil down to three themes:

- What makes us desirable to our customers?

- How will this be feasible for us to run?

- Is the business financially viable?

You need a good answer to each of these questions.

If it’s not desirable or you don’t have a clear set of customers, your marketing will become painful and you’ll need to twist arms to make sales.

If it’s not feasible for you and your team, you risk burnout, key person dependency and will be unable to take a proper break.

If it’s not financially viable, you risk bankruptcy and collapse, and the faster you grow the faster you’ll sink.

As you can see, the canvas will help us draft and understand how each of these three will work, and how they will affect each other.

Why A Canvas?

“Clear writing gives poor thinking nowhere to hide” – Shane Parrish

While some of the terminology will be new for you, the core concepts of each box are well-established in the business world.

The benefit is in laying out your thinking on a single page or board.

A canvas lets you show people your thinking – it draws out some details but also forces you to keep it brief.

It invites good questions – from yourself and your team, and highlights areas that are in need of further thinking or validation.

The canvas isn’t a good presentation tool, but it will give you some natural headings for a presentation.

Don’t show them the model all at once, walk them through the story and your thought process.

Best of all, canvases are disposable – you can shred them and make more whenever you like.

You can draw them on a whiteboard or a big napkin, or share them online through Miro or Mural.

strategyzer.com

How To Get Started

A lot of Western cultures read left-to-right, but we’re actually going to start on the right side of the page – with the customer.

Customers are at the heart of your business; if we don’t know who they are or what they care about, how can we possibly make good choices about the rest of the model?

Secondly, we’ll look at the compelling Value Propositions that each customer appreciates, giving us a sense of what “Product-Market Fit” might look like.

Thirdly, we’ll see how these customers are acquired, delighted and retained, and understand where our next 1,000 customers might come from.

Fourth, the Feasibility boxes on the left; the Key Resources and assets that we use each week, the activities that keep the business moving, and the Partners who do something we’re not good at.

Finally, we look at the numbers – the Revenue Streams from each type of customer and the costs of running each part of the business, and get a sense of whether or not the business will be sustainable.

We suggest that you fill in each box as well as you can, then keep moving.

The process shouldn’t take more than 40 minutes for a first pass, then we can add detail or change our descriptions in the next iterations.

Customers and Problems

Focusing Question: Who are our customers and what do they care about today?

Good businesses are built to consistently serve and delight their customers – that’s what keeps the money coming in, and that’s what keeps the business relevant.

So the first thing we want to understand is who are we serving, and are there several distinct groups of customers?

There are three defining characteristics that make somebody a customer:

1. A customer is someone who is intrigued or motivated - they have an interest or a need, we shouldn’t have to coerce them.

2. A customer is a decision maker – they have some agency and authority to choose who they shop with.

3. A customer is making a purchase - money changes hands.

Three Roles

What you might find is that there are three distinct roles:

- The customer, who makes the purchase decision.

- The end user, who uses your products and services

- The beneficiary, who is better off because of your products and services.

Let’s say you’re selling environmentally friendly drinking straws.

For a copper straw, the customer and end user might be the same person, who cleans and carries the straw with them throughout the day.

For paper straws, the customer might be a fast food restaurant and the end user might be the milkshake buyer.

The end user might hate the paper straw, but the customer (the restaurant) might just want the cheapest option.

In both cases, the beneficiary is the same – the local waterways, which now have fewer plastic straws clogging them up.

Sometimes the customer, end user and beneficiary are all the same person, sometimes it’s two distinct groups, sometimes three groups.

Sometimes the customer never sees the end user or beneficiary (although that doesn’t often go well, it’s hard to make good decisions without their perspectives).

Either way, your job is to accurately label who is who.

What About B2B?

For Business To Business (B2B) sales, the process doesn’t change all that much.

While the whole business might become end users and beneficiaries of your work, in most cases the customer is one or two specific individuals.

These two people are the ones who evaluate their options and make a commitment.

e.g. a salesperson explores options for new software, then brings a recommendation to the founder.

Or maybe it’s a procurement officer who creates a shortlist and brings two options to their boss, who makes the final call.

These two people often use different criteria to make a wise choice for the business, so your job will be to speak each of their languages to make a compelling argument for why they are better off with you.

Describing Customers

There are two ways of describing your customers: Demographics and Psychographics.

Demographics are the broad, basic and clear cut descriptors of people, the type of thing you might fill in on a census form.

e.g. age, postcode/ZIP code, nationality, occupation, income, number of people in their household, etc.

“We sell earrings to people in Kuala Lumpur who have their ears pierced and have moderate disposable income”.

These are straightforward, but can be clumsy.

Psychographics are the invisible, powerful shapers of your personality, like your attitudes, preferences, worldviews and beliefs.

e.g. hobbies, religion, ethics, political views, aesthetic preferences, social status, cultural traditions, taste in media, etc.

“We sell earrings to people who like handmade crafts, bold chunky jewellery that is made by refugees”

These two work well in tandem – we want some of each descriptor when talking about each customer segment.

These help us understand who might be considering shopping with us (i.e. they might need to be in a particular industry or live/work within 50km of your business), as well as the preferences that will lead them to choose you over other competing options (quality, story, ethics, how it makes them look, how it makes them feel, etc).

We can also describe their level of sophistication in buying these types of goods and services.

Have they bought this sort of thing before?

Are they learning as they go?

Do they know the industry language?

Do they know what they want that might have been missing from previous purchases?

Each presents their own challenges and opportunities, but we’ll need to talk to them differently.

Sophisticated customers value a knowledgeable salesperson, unsophisticated customers value a patient salesperson.

High Value Problems

In particular, we want to serve customers who have “High Value Problems”.

Strategyzer use four helpful criteria for these:

1. A high value problem is important to the customer; they want or need a solution and will commit some time to find the right option.

2. A high value problem is tangible to the customer; they can articulate that they need something, rather than just having a vague interest or unease with what they already have.

3. A high value problem is lucrative; customers have a decent budget to spend, they are not assuming it will be given to them for free.

4. A high value problem is unsatisfied; they don’t have a good enough option already.

That might sound like a lot, but have a look at the opposite of each of them:

- If the problem isn’t important, customers will quickly lose interest and won’t follow through on the purchase.

- If the problem isn’t tangible to them, they’ll go around in circles or get decision paralysis.

- If the problem isn’t lucrative, you won’t be able to build a sustainable company.

- If the problem is already solved well-enough by a rival, customers are unlikely to switch to your brand.

That’s why we need all four.

Finding Fit

In the early days of a startup, an entrepreneur will go looking for “Customer-Problem Fit”.

This is the match between a real customers and a high value problem, or in other words “does anybody care?”.

When a real customer has a real interest, your startup has a fighting chance – an opportunity to design something that they would love, then get in front of them to make a compelling pitch.

Ideally, you want to find a decent pool of these customers, who will become the cliché “lifeblood” of your business.

If you can’t identify who these customers might be, or what problems they might care strongly about, then you’re in research mode not growth mode.

Traps

Be wary whenever you hear someone say “Everyone is our customer”.

It sounds lovely but it’s almost impossible – how many brands can you name that appeal to everyone?

You are not everyone’s cup of tea and you don’t need to be either.

You want to be some people’s favourite cup of tea.

Be wary when you can’t attach a real name to a customer segment – don’t just write “corporates” or “parents”.

You should be able to see real people who are the prototype or symbol of this group, making it much easier to visualise who these customers are and what they’re likely to appreciate.

Be wary when you can’t identify a customer need or pain point – it usually means you’ve got the wrong customer or you don’t know them well enough.

Value Propositions

Focusing Question: what is the good reason and the real reason why people choose us?

A Value Proposition is the underlying benefit that a customer gets when they shop with you.

It’s the itch that you scratch, the pain you relieve or the improvements you bring them.

Sometimes this is a straightforward, practical benefit, and sometimes this is a complex set of stories based on people’s personalities and aspirations.

e.g. For you and I, the Value Proposition of a Band-Aid is that a cut heals faster, or you avoid a blister or an infection.

But to a three-year-old, the Value Proposition of a Band-Aid is that it has pictures of The Wiggles on it, immediately making it a proud fashion accessory.

The Value Proposition of a $90 watch is that you’ll always know the time.

But that’s not the Value Proposition for a $20,000 Rolex, which is more likely based on status and exclusivity.

They say that behind every decision are two reasons – the good one and the real one.

Maybe you wish that weren’t true, but check your own lived experiences and see if you agree.

Customers have all sorts of bizarre reasons for doing what they do and making their purchase decisions.

Sometimes it’s because we don’t like saying our reasons out loud (to look good, to impress my boss, to save money where nobody is looking, to get a comfier seat on the plane, to win bragging rights over a rival), or because we don’t have a good reason and need to make a choice (picking the bank your parents used, choosing the brand that you saw advertised on TV, literally picking a book by its cover).

Either way, we want give customers what they want, then help them in justifying their decision.

Finding The Truth

Customers are notorious liars, especially when you ask them about future behaviours.

They invent lovely stories and promises about what they would do, but we get a better sense of the truth when we ask them what they did last time.

A great example is to ask someone about how they went about choosing their car.

Where did they look?

What were their criteria?

What was a deal-breaker and what was a bonus?

What were they choosing between?

What was the tie-breaker for why they chose one over another?

What you’ll likely observe is that instead of talking about features (alloy wheels, roof racks, engine size), they were drawn to the benefits (reliable, economical, fits with my hobbies, makes me look cool).

With more than fifty brands of car and hundreds of models to choose from, customers need to make some bold sweeping decisions, even just to narrow down their options to a final three.

By learning how they made these decisions, we get an insight into what they value and what might entice them to shop with us in the future.

You Can’t Have Eleven Reasons

While we don’t like to admit it, our tendency is to have an emotional response to a situation, then support our emotions with a logical rationalisation.

i.e. you can argue all day that the new Google Pixel phone is technically superior to the new iPhone, and it won’t change an Apple fan’s mind.

The Apple fan has already decided that they’re staying with Apple, so when their phone breaks or dies, they’ll choose between iPhone models, not between brands, and they’re probably not going to compare processing chips or camera resolutions.

Each customer segment will likely have 2-3 big Value Propositions that matter to them.

If you have four different customer segments, that might mean there are up to 9 or 10 Value Propositions, but each customer is unlikely to appreciate all 10.

The best way to illustrate this on your canvas is to colour-code your Value Propositions to your Customer Segments – highlighting which customers care about which benefits.

Traps

Be wary when you find yourself writing benefits that you hope customers will appreciate, rather than ones you’ve heard them appreciate.

Be wary when you haven’t interviewed real people – read The Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick and learn how to hold natural conversations without feeling weird.

Customer Relationships

Focusing Question: How will customers come to know, like and trust our business?

Customer Relationships describe how you plan to treat your customers, both to entice them, engage them and keep them coming back in the future.

There’s no single perfect way to do this, it depends on your customer, your product, your Value Proposition and how you’d like to treat people.

Some relationships are short, and some relationships are long.

Some relationships are personal, and some are completely automated.

Some relationships are all about acquiring customers who then stay put, and some are all about retaining customers who have shopped with you in the past.

Some relationships are cold or formal, and some are friendly or relaxed.

And some are in between.

It’s tricky because building and maintaining relationships is expensive (time, energy, perks and marketing costs), but these are also lucrative.

Loyal customers provide sustainable revenue, but they require a lot of maintenance, so you’ll need to decide how much work you think is necessary to keep people happy and to stay on the front of customers minds.

Know, Like and Trust

A neat framework to think about is Know, Like and Trust:

- How will people know that our business exists?

- What will help them to like what we do?

- How will we show people that our brand can be trusted?

Each of these three factors plays a huge role in your sales growth.

If nobody knows you exist, they can’t shop with you.

If they know you exist and they don’t like you, they won’t consider you and will scare away other prospective customers.

If they know you exist, like you but don’t feel you are trustworthy, they’ll go elsewhere for bigger purchases.

Improving any of these three will have a positive effect on your sales, but it’s even better if you deliberately work on the weakest area – this removes a bottleneck.

Traps

Be wary when you assume customers will come back again in the future if you can’t say why or if you have no ongoing contact.

Be wary if you don’t have a clear Customer Journey Map for each Customer Segment, since you won’t know how it feels to shop with your business.

Channels

Focusing Question: How do we acquire new customers and give people what they want?

Now that we know who our customers are, what they care about and how we want to treat them, we’ll be choosing two types of Channels – the way in which people hear about our offer, and the way in which we deliver our offer.

Sometimes they are one and the same, but in a lot of cases these are quite different.

A Channel is a medium, your preferred way of reaching people.

You’re unlikely to invent a new Channel, you’ll be choosing which current options make the most sense for your market and your Value Proposition.

Think about your recent purchases – how did you first hear about the company, and how did they give you what you wanted?

e.g. You heard them advertise on a podcast, then they sent you parcels in the post.

You walked past their beautiful shopfront, then tried on clothes in their showroom.

You ordered a book online, which was immediately available on your e-reader.

You heard a recommendation from a friend, then ordered something over the phone.

You saw an ad on Instagram, then attended their class in-person.

“Good” or “Bad” is all about customer perception and preference.

Some people love online shopping, some people want to see and touch products for themselves.

Some people want to google a solution within eight seconds, some people want to go through a detailed comparison process.

Some people like the quickest option, some people like standing in a queue.

Some people want to pay the lowest price, some people want convenience.

Our advice is to think through all of your options, then run some experiments or build some prototypes.

If you think customers will shop online, make a landing page and test it out.

If it’s your social media channels, start putting up content and running ads.

If it’s a showroom, try a pop-up or shared space and experiment with layouts.

Traps

Be wary if you’ve listed twelve channels in this little box, it’s impossible to do them all to a high standard.

Be wary if you’ve ruled out a channel without thinking it through – what would your competitors do?

Key Resources

Focusing Question: Where does our strength come from?

Our Canvas has a lot of claims on the right-hand side; promises around Value Propositions, how we’ll treat customers and how we’ll run our channels.

Now we get to think about how we’ll deliver on those promises, and the answer starts with our assets.

Assets are the things your business owns that let it do valuable work.

These might be physical objects, special people, a good reputation or your exclusive knowledge – whatever gives you an edge over your competitors and is required to serve your customers.

Key Resources refers to the most valuable assets which, if removed, would hurt your capacity to keep operating.

We want to understand them so that we can value and defend them, or else there will be huge vulnerabilities in the business model.

There are four main types of Key Resource:

1. Physical Assets – the tangible equipment and inventory that you need to serve your customers.

This might be machinery, tools, your physical space, your inventory of products, anything you’d be devastated about losing in a fire.

Specifically, we want to list things that are hard to substitute or replace – if any shopfront would suit you just fine, then shopfronts might not be Key Resources.

2. Essential People – specific individuals who bring a unique contribution to the business, who would need to be replaced with someone equally talented.

This might be some of your founding team, your top salespeople, your content creators, anyone whose personal abilities are integral to your business delighting your audience.

3. Brand Assets & Reputation – gaining an advantage in the market because of your good name and credibility.

Do people choose you over your competitors because of your track record? Does your brand give you a head start in new markets?

How bad would you be affected by a scandal attached to your name?

4. Intellectual Property – the insights, recipes and methodologies that help you create a better product/service than your competitors.

This is when you know something that other people don’t, allowing you to create a different result for your customers.

For example, there’s a pizza place in suburban Melbourne that claims to have won “World’s Best Margherita Pizza” from some sort of competition in Italy a few years ago.

The place gained enormous credibility from this award, and opened several new stores.

It’s a good Value Proposition, and you can see here how that fits in our Key Resources box.

They have talented people, with the know-how to make a better margherita pizza, and that reputation sits with the business rather than the chefs (whose names aren’t advertised).

We actually have no idea if the pizza competition is real, or if the winning chefs are still in the business, but the claim of “World’s Best Margherita” still lingers and it brings a crowd every day.

Assets should do the heavy lifting for you – they give you the ability to take a day off, to hire new people and turn them into great team members, to dream up new products and services that are better than the competition, and to attract new customers to your Channels.

Without assets, you’ll have to do everything yourself, and that gets tiring very quickly.

You only have room to list 6-8 points in the box, so think about which elements of your work are truly essential or irreplaceable.

When you find them, have a think about how you might guard them.

Is it by retaining good people, recruiting and training new staff, documenting your special magic, actively building your reputation, maintaining your physical assets, etc?

These assets give you strength and a competitive advantage – look after them and they’ll look after you.

Traps

Be wary when you list everyone’s name – is the model really dependent on that many specific individuals?

Be wary when you can’t explain how these resources contribute to the right-hand side of the canvas; if they’re not giving you an edge, they’re probably not “Key”.

Be wary when there is no “plan B” for replacing these resources, as it makes you vulnerable to any sort of change.

Key Activities

Focusing Question: How do we consistently follow through with our promises?

In an active business, there is always an abundance of “good” uses for your time.

Therefore, a clever entrepreneur will need to make very intentional trade-off decisions for how the team will spend their time and how they will focus their concentration.

Some activities will be disproportionately valuable to the business – they are the things that create a competitive advantage, keep bringing in new customers, keep old customers engaged, and help you proactively find ways of staying relevant.

For example, a Key Activity might be time spent on customer research, on inventing new menu items, in forming/maintaining partnerships, running your sales channels, recruiting/training new team members, or calling existing customers on the phone.

Or another way of looking at it – the absence of each of these might lead to trouble; stalling your progress and creating vulnerabilities.

A lot of these Key Activities come about naturally or by accident – the founders scramble to keep everything running smoothly, then take note of what made a meaningful difference.

Eventually you want these to be built into systems, and as Michael Gerber says:

“Systems run the business and people run the systems”.

A business owner is responsible for finding/designing/implementing a system that works, then they need to hire the right people to run those systems.

Remember, if you can’t trust someone else to run the system in your absence, you haven’t built a business, you’ve built a job.

e.g. you might have a system for how you attract new customers, and a system for how you take their order and keep them happy while they’re waiting.

You might have a system for training new team members, and a system for how you innovate new products and services.

If these currently depend on one single person in your company, then you company is very vulnerable and that person is unlikely to be able to take a proper holiday.

Instead, we want talented people to shape and install good systems, freeing them up to grow the business.

Traps

Be wary when you have high-touch relationships on the right-hand side of the canvas, with no corresponding Key Activity to actually do that work each week.

Be wary when you have twenty Key Activities – it usually suggest you haven’t prioritised your time.

Be wary when your Key Activities all fall on one key person, since your business does not own them, cannot clone them and cannot rely on them in the future.

Key Partners

Focusing Question: Who are our suppliers and who are our allies?

You aren’t alone – there are so many good people out there who can help you succeed, and let you focus on where you’re strongest.

These people and organisations are called Key Partners, the people who take some responsibility off your shoulders.

These partnerships let you decide where you want to be a specialist, and where you want to outsource something that isn’t going to be a strength.

You’ll have lots of different partners, but there are two main categories:

Suppliers – people in a different part of the Value Chain, like those who make your raw materials, who host your website, who own your building, who handle your logistics, etc.

Allies – people who support your cause or your brand, who send traffic your way, who fund or support your growth, and with whom you can form joint ventures or collaborations.

While there’s not a huge difference for the canvas, the two big variances are power dynamics and money changing hands.

A business can (and sometimes needs to) be a bit ruthless with suppliers; changing them over if they are not performing.

You (the customer) can take your business elsewhere, since you are paying them for something clearly articulated in a contract.

On the other hand, you might have your local government as an ally, but the relationship is less transactional and a bit more delicate.

It’s unlikely you’ll declare that you’re swapping cities to join a different local government, and you can’t hold people accountable in supporting you.

You can be nice to your allies, but you can’t buy them or control them.

The interesting question here is “How do these partners affect our model?”.

Are you dependent on them for a steady stream of customers?

Are they the linchpin in your work?

Do they know something or own something that other suppliers can’t bring?

Are we doing enough to retain them?

Should we be doing more in-house?

Should we outsource more activities to talented partners?

Traps

Be wary when your business depends on the whim of a single Key Partner.

Be wary when you don’t have a Plan B or Plan C if your supplier suddenly can’t deliver what you need.

Be wary when you have no outsourcing or partnerships – it might suggest you’re taking on too much responsibility.

Cost Structure

Focusing Question: Where do we commit our money?

By this point, our canvas is full of promises and commitments, all of which come at some sort of cost.

It might be through wages for people’s time and energy, the ingredients you buy, the costs attached to each of your channels, or the suppliers you’re paying.

Good.

It’s good to spend money on the elements that drive your sales and delight your customers.

What we don’t want is to commit money to things that aren’t essential to the customer or our systems, or when we commit too much money to something that comes back to haunt us.

For example, hiring a large team too quickly can severely limit your cash runway.

The same applies to making huge quantities of your products in order to lower the per-unit costs – it makes sense if you sell them all, but it takes away all of your spare cash and increases the urgency to make sales.

We want to understand where our money goes, how much we spend and how often we spend it.

Some costs will be fixed, and some will be variable.

Some are once-off, and some are recurring.

Some require an up-front commitment, some let us spend money after we’ve earned money.

Our job is to accurately label our costs, then step back and look for opportunities and red flags.

We might see opportunities to give some more responsibility to a partner – paying them for a finished product rather than taking the financial risk ourselves.

Or we might spot a bottleneck in our cashflow, as we buy too much in bulk without any certainty that we’ll make enough sales in a short time.

Traps

Be wary when you can’t see where your money goes – everyone on the team should have a basic understanding of how money moves through the business.

Be wary when you overcommit to big bulk orders – it makes you vulnerable to any changes in the market.

Be wary when your costs are growing faster than your revenues – the more you sell, the faster you lose money.

Revenue Streams

Focusing Question: How does money flow into the business?

The difference between a hobby and a business is revenue.

Money is the fuel of choices, and it’s what keeps your business going.

For that reason, an entrepreneur needs to be hyper-clear on where their revenue comes from, how often and in what amounts.

When you design a business model, you are designing revenue streams – thinking up ways for happy customers to spend their money, and there’s a huge range of options available to you.

The first big question here is “Who pays what?”.

We can look to our Customer Segments box for answers – which decision makers are making a purchase, and in what format?

Are they signing up for a subscription or membership?

Do they own the product or do they rent it?

Are they buying one big bundle, or lots of smaller options?

You might find that different customers shop in different ways – some might want to put a toe in the water, some might buy a lot upfront, some might want an ongoing service or subscription.

The next question is “How much should we charge?”.

Pricing is a loaded topic because it’s a mix of economics, psychology, philosophy, market analysis and signalling.

i.e. sometimes you might want to be cheap because it wins more customers, or because it makes you inclusive, but sometimes cheap suggests inferiority.

Sometimes you might want to be expensive because it wins higher value customers, or because it makes you more margin, or because it makes you seem like a premium choice, but sometimes high price excludes a large portion of the market.

There are three main ways of setting prices:

· Cost-Plus: taking your costs, adding a margin, that’s the price.

· Market Based: looking at your competitors, identifying a top and bottom range of acceptable prices, then choosing where in that range you’d like to sit.

· Value Based: Understanding what your Value Proposition is worth to your customer, then using that to set prices, irrespective of what your true costs are.

For example, a supermarket uses Cost-Plus pricing, and sells Coca Cola for $2.

A café uses Market Based pricing, and sells Coca Cola for $3 - $4.50.

A stadium or airport use Value Based pricing, and sell Coca Cola for $6.

The product is identical, but the circumstances are different, and so is what customers are happy to pay; good luck charging $6 in a supermarket.

You’ll want to explore all three of these to determine the right price.

If it’s below your costs, you go broke.

If it’s much higher or much lower than the market, you might not attract your target audience.

If it’s higher than the value it offers customers, they will shop elsewhere or choose to do nothing.

The final question is “How often do they come back?”.

Repeat business is the ultimate compliment – customers come back out of self-interest, which is far more honest than them saying nice things to you.

Repeat business is also what keeps companies alive, since it is so much cheaper to retain customers than win new ones.

It’s highly lucrative to get this right – you make substantially more revenue if you can re-entice or re-acquire customers to either make the same purchase again, or make the next logical purchase, or to encourage people around them to choose your brand.

This is why so many businesses send you emails, give out loyalty cards, create referral programs, or follow you up after a period of time.

Have a think about how you might keep customers happier for longer, whether it’s through a membership, extension products/services, engaging marketing, well-timed discounts, etc.

The nice thing about this formula (Customers x Price x Return Frequency) is that fixing any one of those numbers will have a huge effect on your revenue.

If you have a fixed number of customers, pricing and re-engagement are golden opportunities.

If your prices are hard to move, it might be worth exploring new Customer Segments.

But the most important thing you can have right now is clarity – how do customers behave, what do they spend, what triggers them to leave, and where are our options for improvement.

Ta Da!

Congratulations!

You now have an imperfect but complete Business Model Canvas.

To be honest, this is usually an underwhelming moment; people are often mentally drained and half-satisfied with how their business looks on the page.

No matter!

The best thing you can do now is to stop writing – go for a walk, a coffee, a meal, a workout, anything to clear your mind.

The canvas will be here when you’re feeling refreshed.

You’re waiting for an itch – and it will happen.

The itch is the nagging sense that:

· There are more Customer Segments waiting to be discovered

· You thought of another Value Proposition

· You’ve identified an interesting new Channel

· You have ideas of other Key Resources that would make life easier

· You’ve articulated what your best team members do well that you’d like future staff to copy

· You’ve looked at your financials and now have some “rule of thumb” figures

· You’ve thought of a totally new business idea

Lucky for you, the second Canvas is much quicker and clearer – it’ll probably take you 40% as long as the first one.

It usually takes two or three iterations for it to properly reflect your business, and you probably can’t do these all in the same day.

What To Do Next

A Business Model Canvas doesn’t magically “fix” or “transform” anything.

What it does is create clarity, reveal opportunities and help you talk about your company.

Having worked with a lot of entrepreneurs through this process, here are the next steps that let you take full advantage of your newfound clarity.

Customer Interviews

Your customer descriptions are wrong, and we don’t know which parts are wrong.

Rather than make guesses from your office, the best thing we can do is go and talk to these customers, to learn more about their preferences, priorities and natural behaviours.

No contrived focus groups, no awful surveys, just good questions in conversation about their past behaviour and past purchases.

The book you want to read next is called The Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick, which outlines how to ask good questions of people who are genuinely your target customer (as opposed to getting empty compliments from people who were never going to buy from you).

The book is short, funny, beautifully written and is surprisingly cheap.

Fair warning, customer interviews can feel confronting, but they have worked for 100% of our clients.

Literally everyone who does these is glad they did them.

Prototypes and Pretotypes

Prototypes bring your idea to life – it’s much easier to understand something when you can see it, touch it and experience it.

When we say “understand”, that might mean realising a flaw in the model, being reassured that customers love the Value Proposition, discovering that your costs will be higher than anticipated, or realising that you actually want to build something slightly different.

The earlier you can have these moments, the better.

There are several sorts of prototypes you can build, from physical mock-ups to paper versions of apps, one-page websites or hosting a pop-up experience.

Then there are “Pretotypes”, which are even earlier versions of your idea.

For example, you might run an ad or make a poster for your product/service, promote it and measure interest.

You don’t need to actually make the product or deliver the service, you’re gauging demand and seeing who clicks on what.

No demand, no problem – you haven’t invested time and money into building something that you can’t sell.

High demand, high confidence – you’re now more comfortable investing time and money into making the next prototypes, reassured by the demand you’ve just seen.

The book you want to read is called Testing Business Ideas by David J Bland and Alexander Osterwalder, it’s like a cookbook of different styles of tests and prototypes.

Identifying Assumptions

Just because you write something on a canvas doesn’t mean it’s true.

Your Business Model is full of assumptions, and that’s ok, but we now need to separate fact from fiction.

You’ve made assumptions about Customer Segments – who is the decision maker, how they make a choice, what Value Propositions they care about, etc.

You’ve made assumptions about Channels and Relationships – how you’ll find people, how you can serve them, and which Channels are disproportionately effective (realistically it might be that 20% of your Channels bring in 80% of your Revenue Streams).

You’ve made assumptions about your operations, such as the capacity of your team and Key Partners, how long your Key Activities will take and how expensive your Key Resources are to maintain.

You’ve made assumptions about your financials, how much margin you make from each sale, how much customers are willing and able to pay, and how long it will take for you to break even.

The earlier you validate these assumptions, the better you’ll feel.

If there’s a problem, when do you want to find out?

A neat way to keep track of these is with a traffic light dot system:

· A red dot next to the untested assumptions

· A yellow dot next to the ones in progress

· A green dot next to those you’ve confirmed and validated

New Models

There isn’t one single version of your future business – there are all sorts of models you could choose to pursue, each with their own focus and speciality.

We want to be able to see these, compare and contrast them, so that we can make good choices about which one or two we want to build next.

It might be that instead of trying to “have your cake and eat it too”, what you really want is “two small cakes” – two specialist businesses that are each excellent at something, without compromise or confusion by trying to fit them together.

It can help to start with a design question, like:

· What if we had to do everything online?

· What if we only targeted the top/bottom of the market?

· What if we just did wholesale/retail?

· What if we gave the core product away for free?

· What if we built a club/membership?

· What if we thought 10x bigger?

· What if we just sold one thing?

The Business Model Canvas helps to translate a big idea onto a page, and the more of them you create, the more choices you’ll have and the more creative opportunities you’ll see.